| Actor: Mohsen Makhmalbaf Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Family Life Studio: New Yorker Video Format: DVD - Color,Widescreen - Closed-captioned DVD Release Date: 07/19/2005 Release Year: 2005 Run Time: 1hr 15min Screens: Color,Widescreen Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 6 MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Languages: Persian Subtitles: English |

Search - The Silence on DVD

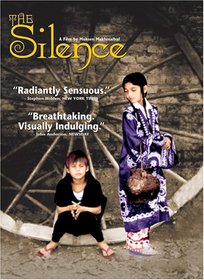

| The Silence Actor: Mohsen Makhmalbaf Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama NR 2005 1hr 15min ""Radiantly Sensuous." ?Stephen Holden, The New York Times "Breathtaking. Visually Indulging." ?John Anderson, Newsday "A flip-book of gorgeous, lyrical images." ?Wesley Morris, San Francisco Examiner "Funny and profound.... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

|

Movie Reviews"If you close your eyes, you'll learn better" tuberacer | Honolulu, Hi. | 11/08/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) ""The Silence" tells the story of the blind boy Korshid who needs to make money from his musical instrument tuning job so that he and his abandoned mother can pay the rent before they are thrown out by their landlord at the end of the month. Korshid's problem is that he is easily distracted by beautiful sounds and wanders off in pursuit of them, making him late for work and thereby, susceptible to getting fired by his boss. Nadereh, a girl probably close to the age of puberty who also works for the boss, is his escort and friend. You should know that since she has not yet reached puberty, Nadereh does not yet have to wear a headscarf like all the other women we see in this Central Asian Islamic society. Nadereh, like Korshid, loves beautiful things and thus we are introduced to the main conflict of the story. Korshid needs to work to make money, but he doesn't because of the distracting beauty of some parts of the world he hears, smells, feels, and tastes around him. Nadereh clings to the delights of her girlhood--delights which would be deemed too trivial or even indecent for a woman, but excusable for the time being since she is still considered a child--but official adulthood is probably looming close for her. It seems all the other women just above her age are busy struggling to bake and sell their bread, or their colorful produce--and all of them are headscarved. Makhmalbaf assaults us with beauty in his movie--bright sunlit scenes with women in colorful flower print headscarves and clothing selling bright red onions and cherries. He gives us closeups of young girls' clear chins and pink lips. He decks out scenes with yellow leaves and red flower petal fingernails and noisy markets with songs on the radio, and with intricate music played on handcrafted instruments--on the streets, in the restaurant, on the bus, by the side of the river. He goes even beyond that to show us the beauty in song and dance that is inspired by the natural world, and the beauty of being able to communicate with the natural world through song and music, and then even the beauty of allowing oneself to become one with the natural world. Makhmalbaf brings out mirrors to reflect the beauty of the world and the power of the sun--a possession even for the poor. But don't be lulled into thinking this is simply a movie about the conflict of having to work and wanting to enjoy life. Makhmalbaf is not such a simple moviemaker. He's the man who formed an Islamic militia when in his teens, was imprisoned, and after the Iranian revolution, turned away from politics to engage in the arts.. He's the man who made the socially distressing movie "The Cyclist" and the greatly praised "Kandahar." "The Silence" is a very bold, even courageous film. Consider the situation. Iranian filmmakers have many restrictions on what they can show and do, just as the Iranian people have restrictions on what they can show and do. You could easily see the Korshid character who struggles for the beautiful as a self-portrait for Makhmalbaf. Just like Korshid, Makhmalbaf, from the age of eight, worked to support his single mother, doing all kinds of menial jobs, and the enslavement to money, and the monotonous, dull, regimented repetition of that kind of work and its affect upon people--all due to the requirements of a monetary system--is a major theme in this movie. Isn't it ironic, though, to see Makhmalbaf in Korshid? The movie director who gives us beautiful visual images in a child who tells us to close our eyes to learn better. The acting in this movie is a little stilted at times, but that adds to the parable-like structure of the story. The mother seems more a type than a full character--there to place the timed questions. Some of the child actors and actresses, on the other hand, seem wonderfully natural in their parts. Iranian filmmakers make a lot of films about children because they are not as restricted with child characters by the Iranian censors on certain subject matter as they are with adult characters. Like Nadereh, children are allowed to indulge more. It is overlooked because of their age. I think there's one moment in this film where Makhmalbaf really plays with our mind using this child/adult compromise. There's a transition moment, switching from one series of images and thoughts to another during one of the scenes that, if they had been adult characters in the typical Western adult movie, the visuals of the transition would have made you assume that, during the unknown interval of time represented by the transition, the two characters had engaged in impassioned physical intimacy. They didn't, of course--they're innocent children--but you can't help the immediate sense--it's a kind of knee-jerk reaction caused by the visuals--that lovemaking did happen because you've seen this kind of visual transition so many times before with adult characters in other movies who did just engage in lovemaking--as you were, in those movies, rightly supposed to have assumed. I think Makhmalbaf tosses in this teasing visual transition as a kind of joke--a little laugh at how well we're trained to assume things through cinematic visual tradition, and a joking snub at the censors. He's simply, for the briefest moment, putting a PG-rated Bergman moment in his film, toying with his legal restrictions, humoring himself with what he can do anyway. If they had been adult characters, this would have been the typical movie situation: a man and a woman, running together for whatever reason, both victimized by the same oppression, take a moment out of the running to succumb to their mutual attraction, to at last embrace, to at last make love. But this is not a film about adults, right? That can't happen with these characters. He can't make that moment happen. Or did he? You'll probably know the moment I'm talking about when you see it. You might call it, "Splendor in the Leaves." I think Makhmalbaf--a very conscious filmaker--mischievously manipulates our minds for the moment this way. He knowingly puts in a Western adult-rated cinematic convention despite it's obvious inappropriateness for this movie about children. It's his own inside joke. He's laughing at the assumption he knows it will create in us and saying, "Ha, ha, gotcha!" He gets away with it and there's nothing we or the censors can do about it because there's really nothing to point at and say, that's obscene! After all, it all happens semi-consciously in our heads, not in the film at all. They're just children under the trees. What in the world were we thinking? Who just committed a crime? Makhmalbaf or us, the viewers? It's a kind of wake-up call. Who's thinking here, and who's not? Who's paying attention and who's lazily riding along on assumptions? It's so simple and so subtle, yet in hindsight, so delightfully brazen and contentious. It's a real slap in all our faces, and perhaps, a sad reminder of the tight restrictions on his creative process that he suffers--this inside joke a kind of gallows humor--having to use children to say things he might rather have said using adults, and since he can't use adults, he can't really say so many things. Also consider the headscarves. Korshid's mother's headscarf is one of the first things we see in the movie when she grabs it to put it on so she can answer the knock-knock-knock-knoock of the man at the door who's demanding payment. Like the movies Makhmalbaf makes, the headscarf is officially approved, except these women's bold designs and colors in their clothing and coverings, at the same time, seem rebellious against the restrictions in their sheer beauty. How far can they push the envelope with their designs? At what point would their designs step over the line? When would they be considered contentious? When would they be considered sacrilegious, and for an Iranian viewer, when would they be considered counter-revolutionary? Questions which are always on Makhmalbaf's mind while making his movies, I'm sure. This is a man who wants his hands untied. Why set this story in Tajikistan rather than Iran? I suggest you consider the headscarves as a way to the answer. Everywhere in the movie there are examples of the arts being maintained because they are natural and because they are traditional. There are even large figurative sculptures about bounty and abundance in this Islamic setting. Strict Islam, of course, bans figurative representation because of the threat of idolatry, and even filmmaking and photography tread dangerously on this ban with some Islamic theosophists. Then there is the man with the gun who forces women to put on their scarves--the representative of the ruling order--the soldier who, nevertheless, when he's not enforcing the law, is himself a musician--a man who also can produce beauty. It comes natural. It is the essence of being humbly human. There is one other thing I would suggest you keep in mind while watching this film--the significance of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. There are two legends of what the famous first four notes of the Symphony are about. One says that Beethoven got the four notes from listening to the song of the YellowHammer bird in a park one day. The other legend says that the four notes mean, "Fate is knocking at the door." Beethoven wrote the Symphony while the French Revolution via Napoleon was marching across Europe and many consider the music to be a depiction of change coming forcefully, unstoppable. Just what is this very quintessential Western music doing in this film? Why the repetition of the four notes in various ways in various settings? Why is Korshid insistent on hearing them? Does he think them simply beautiful? And then, of course, there's the title. Why call this movie, "The Silence"? Strange, since beautiful noise is Korshid's primary passion. When is there silence and what does it mean? What does it mean maybe in the broader sense? There's so much going on in this deceptively simple-seeming story that I could go on and on. This is the rich, confident, and demanding work of a master moviemaker. One of the great cinema artists of our time. "The Silence" is a small, tight film that sings and shouts--in the key of C minor, Op. 67--and is worth watching again and again to catch every little nuance, every bold color, every bright sound." Unseen Makhmalbaf Kristopher Kincaid | Vietnam | 10/11/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "Mohsen Makhmalbaf has had a few distinct phases. First there was the gritty-realist beginning (as in The Cyclist), then the self-reflexive cinematic portrait of Iranian society (Salaam Cinema and A Moment of Innocence), and finally his most recent, the painterly poetic phase. All of these are of interest, and it's too bad that Makhmalbaf - perhaps because he's tried several different styles - doesn't get the respect of Abbas Kiarostami. The Silence is one of the most visually striking films made in the last ten years, and though it's a visual masterpiece there's no denying that the imagery easily outdistances the slight narrative. Still, strange that this film remains so obscure. Shot in remote Tajikstan, it is one of the most remarkable bouquets of color I can remember seeing in a film. For anyone who appreciates the visual pleasures of the cinema or has an interest in obscure locales, Makhmalbaf's film is a stunning achievement." A visually beautiful film about entrancing sounds Phillip G. Poplin | Austin,, TX. USA | 06/02/2007 (4 out of 5 stars) "The blind, ten year old instrument tuner named Khorshid at the center of this film is in love with sounds and rhythms: music, rivers, bees, poetry, a girl's pretty voice. One intriguing sound is enough to peel him off from the business of the day and send him in a new, unplanned direction. A girl named Nadareh watches after Khorshid and helps to keep him from wandering too far, but his job is in jeopardy and he and his Mother are facing eviction. Such temporal concerns are secondary to Khorshid, whose obsession with sound is relentless. The plot is simple, the pace is slow, but this film is beautiful. The imagery is powerful, sensual and provides the viewer with a visual mirror on Khorshid's aural, interior fantasy." Blind but finding happiness with everyday routines D. Kanigan | CT, USA | 04/20/2008 (4 out of 5 stars) "Khorshid is a blind 10 year old boy from Tajikistan who lives with his Mother, who is struggling to eke out an existence and desperately trying to hang on to their hut/home.

Khorshid works as a tuner of music instruments. He is at risk of losing his job as he's often late. He has to travel a long distance by bus and by foot to get to work and he often gets sidetracked by voices, a drumbeat, the touch and feel of bread or fruit, or other sounds and experiences of everyday life in the city. Khorshid, while blind and poor, manages to find peace and happiness in his world. This short movie (75 minutes) can be ploddingly slow and the plot very simple - but the film is visually spectacular with mesmerizing and hypnotizing sounds. You move through the scenes with the blind boy as he experiences life. I find myself reflecting back on this movie weeks later so while the storyline was "basic" - the message hit home. " |