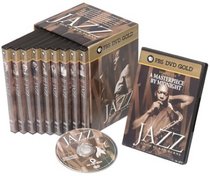

| Actors: Keith David, Charles J. Correll, Freeman F. Gosden, Edward R. Murrow, Richard Nixon Creator: Tricia Reidy Genres: Music Video & Concerts, Educational, Musicals & Performing Arts, Documentary, African American Cinema Sub-Genres: Jazz, Educational, Documentary, History, African American Cinema Studio: PBS Home Video Format: DVD - Black and White,Color - Closed-captioned DVD Release Date: 01/02/2001 Original Release Date: 01/08/2001 Theatrical Release Date: 01/08/2001 Release Year: 2001 Run Time: 19hr 0min Screens: Black and White,Color Number of Discs: 10 SwapaDVD Credits: 10 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 10 Edition: Box set MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Languages: English |

Search - Jazz - A Film by Ken Burns on DVD

| Jazz - A Film by Ken Burns Actors: Keith David, Charles J. Correll, Freeman F. Gosden, Edward R. Murrow, Richard Nixon Genres: Music Video & Concerts, Educational, Musicals & Performing Arts, Documentary, African American Cinema NR 2001 19hr 0min The story, sound, and soul of a nation come together in the most American of art forms: Jazz. Ken Burns, who riveted the nation with The Civil War and Baseball, celebrates the music's soaring achievements, from its origin... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsAn impressive, in-depth course on jazz history! J. Lund | SoCal, USA | 01/08/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "After several days of marathon video viewing, I'm happy (and relieved) that, despite some inevitable imperfections, JAZZ: A FILM BY KEN BURNS is an amazingly broad and detailed exam of the music's history. Despite having read many excellent jazz-related books, I think that video rather than the printed word is the preferred medium to get initial or even remedial exposure to the music, because here you have as the centerpiece the actual audio and video of the art and artists. If you read a book about jazz, you don't have that essential evidence of the music itself, but merely descriptions of it.Why buy the DVD? There is a minor amount of extra footage. More significantly, the program can be altered so that whenever a piece of music appears, one can display the discographical info. As such, one never has to wonder what they are listening to. Furthermore, the sharpness of the DVD video picture and clearness of the audio is a selling point, particularly when you're looking at vintage photos, videos, and audio that are often not in optimal condition. Plus, with the DVD you can watch the series at your own pace.I might have thought beforehand that a series which takes six hours just to get to Armstrong/Hines' 1928 landmark recording WEST END BLUES might be a little too obsessive. Yet I remained riveted to the television screen as jazz's history unfolded, from Buddy Bolden to Cassandra Wilson. Jazz has a VERY compelling history on many levels--emotionally for one given the periodic mist in my eyes. I would have preferred a bit less commentary over the clips of jazz's great artists, but occasionally Burns does let the music speak for itself. I was impressed that we get to know a lot of the primary artists in a fair amount of detail. The likes of Armstrong and Ellington (but surprisingly not Miles Davis) are followed from the beginning to the end of their lives.My first significant exposure to jazz was in the 1970s, and I believe that if this series has an achilles heel, it is that jazz's impact on contemporary popular music could have been examined, which would have provided younger generations a logical entry point that we can relate to, irregardless of our prior degree of exposure to jazz. Instead, the impression-by-omission left here is that jazz has virtually no ties to contemporary pop culture, which I strongly dispute. I think the majority of the viewers of this program are ultimately going to be those who reached adulthood in the 1970s or later, and there is so much that could have been exposed to these generations to indicate that jazz is not a museum piece, but has significant links to contemporary popular culture. For example, I hear a considerable jazz influence on artists as diverse as Stevie Wonder, Sade, various "acid jazz" artists (particularly in Japan--one of many indications of jazz's global influence), early Earth Wind & Fire, Joni Mitchell, Steely Dan, and countless others. Many will compile their list of JAZZ's omissions (Toshiko Akiyoshi would lead mine). Yet even with these relatively minor quibbles, Ken Burns has done the music a great service with this project. I wouldn't be surprised if this series ignites a substantial increase in interest in the music by consumers who otherwise might have never given jazz music much thought." The good, the bad, and the ugly Darin Brown | Goleta, CA United States | 02/23/2001 (3 out of 5 stars) "I think I understand the viewpoints of BOTH the harsh critics and the fanatical supporters of this series. Both have valid points. Both "sides" sometimes fail to understand the points of the other "side" (or fail to even try). Here, I'll try to explain why I think both viewpoints are legitimate.Briefly, what are the good vs. bad qualities of this series?GOOD: Music is often blended extremely well with visual material. There is much great music and great film footage. Anyone new to jazz will be exposed to these. Even those not so new to jazz will find interesting sounds and sights. The commentary by Gary Giddons throughout the series is unusually helpful, insightful and moderate, in contrast to some other commentators (see BAD below). The film is good at telling stories (although many of these blur into legend and myth, see below). This film will be entertaining to the general public; it will expose jazz to many people who would never have gotten into it otherwise. It will widen jazz's audience, and in this sense, it will be good for jazz. I don't know how many people I've seen posting on the internet recently who've said that because of this series, they've decided to buy more jazz CDs, go to some jazz concerts, and buy books on the history of jazz and various musicians. So many people are at least being pointed in the direction of exploring jazz on their own, this in itself is a good thing, which will eventually be more significant than the serious flaws in the series (despite that critics of the series feel otherwise at the moment).BAD: Very often historically inaccurate, blurring the line between history, legend, myth, and cliche. These sins are too numerous to list. See Francis Davis's recent excellent review in the Atlantic online. ("I Hear America Scatting", January 2001) The narration is full of simple, declarative _subjective_ statements which are presented as if they were concrete facts. The history of jazz is presented as closed, undisputed, and final, rather than open, alive, and fresh. The film is awash in hyperbole, overstatement, and blind sentimentality, which takes the place of solid analysis and explanation. Figures (esp. Armstrong and Ellington) are deified to such a degree that the deification they receive completely overshadows their musicianship, and hence trivializes any legitimate attempts to explain or describe their true impact. The music of both Armstrong and Ellington is enough to defend their contributions as some of the most important in jazz history; we don't need to be told that Armstrong "was sent from heaven to make people happy". The film has a definite bias in promoting the Marsalis-Crouch viewpoint. This is perhaps the most serious flaw -- Burns is trying to find abstract ideas (America, freedom, race, democracy, etc.) in jazz music, and ends up injecting race to an extent that is not accurate with social history. There's nothing wrong with having a viewpoint. The problem comes in presenting this viewpoint in such a way that the viewer is never aware that there IS a viewpoint IN THE FIRST PLACE. Evidence of this comes from the stream of newbies to jazz who, after watching the series, confidently reply to the critics: "But this series is well made after all, because NOW I have a good introduction to the history of jazz." Really. How could you KNOW, if this is your ONLY significant exposure to jazz? And that's the big problem, is that the series always gives the impression that it's "objective", giving viewers a false sense of security. The scat singing is annoying. And of course, the impression that jazz died and suddenly reawakened when Wynton Marsalis picked up a horn is patronizing.So, the series is good as mainstream entertainment and as a vehicle for getting the general public very excited about a neglected art form. The series is bad as an accurate, even somewhat objective history of jazz, and it's conceived with a social agenda that severely compromises its presentation.My own (admittedly biased) advice to jazz newbies interested in this series: I would rent the series from the videostore. Watch it, enjoy it, love it, and take it with a ton of salt. Then, take the money you would have spent on buying the series, and get several good CDs that interest you. Also, buy the three following excellent books, which together will give you a much richer, much more insightful, much more accurate, and much more representative history of this art form:The History of Jazz, by Ted GiolaVisions of Jazz: The First Century, by Gary GiddonsCollected Works: A Journal of Jazz 1954-1999, by Whitney Balliett" A gift to American culture Earl Hazell | New York | 08/29/2002 (5 out of 5 stars) "Let's start with the criticisms and get them out of the way. For one, what you may have heard about Ken Burns skipping a great deal of the past four decades of the history of Jazz is true. He did that, ostensibly, in order to focus on the existential continental drift initiated by the invention of "Free Jazz" by saxophonist Ornette Coleman in 1961, and what that has meant for both the future of the music and its very definition. But yes, the overarching presence of Wynton Marsalis and "the bull in the African-American intellectual's China Shop" writer Stanley Crouch (the Wagner/Nietzsche duo of the jazz world) is evidence that the condensing of the past forty years onto one disk (or a little more than two of the nineteen plus hours of this documentary) is actually a function of their philosophy. Not, per se, any embryonic one of Ken's (who said repeatedly he knew little of the subject matter before taking this on) or the foundational perspective of every jazz musician. Crouch and Marsalis' perspective (as many know) to a large degree excludes much of what happened after 1961 via declaring it not legitimately being part of the art form that is Jazz. My second complaint--a more important one: the glory of doing a documentary on a living art form is that there are so many seminal artists of it still performing today, let alone still living and wanting to talk about it. It was amazing to hear such special communicators like Wynton, Stanley Crouch, Gerald Early, Giddins, Jon Hendricks, Branford, Charlie Parker's first drummer Stan Levy, Artie Shaw, or Bird's widow Chan Parker and the like share powerful insights and stories. Yet it could not replace--or even equal in retrospect--the value of hearing from even more living musicians than he interviewed throughout the documentary. For example (if not especially), Max Roach (who I have performed with in New York and Europe, still lives in midtown Manhattan, and is arguably modern jazz' most important percussionist. He is inexplicably absent from this collection, despite his 60 year Protean career and overarching influence being featured on more than two of the ten chapters of this documentary). Or, Jimmy Heath (who took over Coltrane's spot in one of Miles Davis' 50's combos and with whom I studied jazz composition in college: brilliant). Or the incomparable Oscar Peterson: the ultimate jazz pianist link to both the genius of Art Tatum and the early stride pianists of the teens and 20's, connecting us to the dawning of the art form in New York. Or pianist Ahmad Jamal: possibly the biggest influence on the artistry of Miles Davis. Or Dr. Billy Taylor, pianist protege of Ellington--to say the least about his career. Or Sonny Rollins, who is prominently featured on one chapter, and is still gigging around the country--probably as you read this. Or BOBBY MCFERRIN, the Coltrane of jazz singing today, who is unconscionably not mentioned at all in the entire series. Or ORNETTE COLEMAN HIMSELF--the subject of the schism of jazz in its entirety seen on the ninth disk....I could go on; and so could most jazz musicians. The final critique is the history of heroin and drug use in jazz after the 30's Swing period, told brilliantly by Burns throughout the Be-bop and post Be-bop era discs. Told brilliantly, yes. However, the previous disks consistently and responsibly put all of the seminal figures of the art form's quixotic behavior and troubled lives into the profoundly definitive context of the racism and morally schizophrenic social fabric of the 20th century in America. When drugs came up, little to nothing was said about where exactly this heroin trade originated (nationally and internationally speaking), how it began inexorably coming into the Black communities, via what clandestine criminal organizations, etc. In other words, it wasn't for my taste responsibly linked to the same social dynamics he previously underscored. All that said, you simply have to see this entire series to know, despite me giving you a bunch of paragraphs worth of b**ching, why this documentary is worth SIX stars. Ken Burns will be the subject of a documentary himself in the not too distant future, to be sure. His genius in putting this entire series together--blending the drama, pathos and emotional panoramic of great film storytelling with the attention to the historical detail and objective character study of documentary--is, as far as I know, unparalleled. The portrait of Louis Armstrong alone is worth the price of the entire set. Before this DVD series I thought I knew what his contribution to American culture was. Now I know Armstrong was among the greatest of us all, INCLUDING Mark Twain AND the Founding Fathers. Burns work on Ellington, also, will help you lay to rest any difficulty you may have with hearing Duke compared to Copland, Gershwin, Bernstein and all the rest of the American composers--and be found to tower above them. And Burns' work on the early days of jazz is almost overwhelming. And then there is Wynton. Wynton's work on this set is nothing short of poetic. There are moments where his perspectives are so eloquently rendered on camera (even for him) that it nearly forces you to agree with them if you didn't already. There are other moments, while explaining the significance of singular people and the incomprehensible beauty of this music, where he bares his this-is-why-I-play-jazz soul...and you come off feeling as if you are a better person from just listening to it. In one of the later discs, Wynton explains that what keeps musicians playing, giving their entire lives to Jazz, is that it gives them "a taste of what America will be when it becomes ITSELF." "...and it WILL become itself...that's a sweet taste man." Ken Burns' JAZZ--like Jazz itself--is high art. A collector's item for anyone who just loves Music." Provides a very useful orientation Bob Fancher | United States | 02/11/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "Jazz is a relatively recent interest for me--maybe half a dozen years. I'd learned about scattered fragments of jazz, but never developed a systematic understanding, a clear orientation--though a couple of times I'd tried: I bought Gary Giddons' "Visions of Jazz," for instance, which is very good but just didn't capture my imagination. Ken Burns' "Jazz" gave me what I've been wanting for years--a clear, evocative, comprehensive way into the genre as a whole. Okay, it may not be the last word on the history of jazz. Yeah, some things really irritated me--like the slighting, mentioned by many, of Bill Evans, and the excessive excision of many white musicians to make the generally accurate point that jazz springs more from the experience of Black Americans. (Hint to Burns: You make your argument stronger by showing how apparently contrary data fit, not by leaving them out.) But over all, I found this a very helpful overview. And I enjoyed getting to know the biographies of, and the personal relations among, the players. You won't likely get such an orientation from buying a few of the original CDs *instead* of the "Jazz" series. Few of us have the ears or training to discern what's taught in this series. You'd be highly unlikely to realize that, for instance, what was new with Be-Bop is improvising on the underlying chord changes rather than the melody. You'd really have to be perceptive and paying attention to notice what distinguishes Kansas City jazz from New Orleans jazz from New York jazz from West Coast jazz. And *no* album can place *itself* in history. For instance, you cannot learn from listening to an album featuring Coleman Hawkins-or Charlie Christian or Kenny Clarke--that *before* that album people played very differently. In short, you'd have to be far better trained musically and far more observant than most of us are, and listen to dozens (if not hundreds) of albums, to learn what this series teaches.As I watched over a period of a couple of weeks, I bought several of the CDs that Burns produced to survey the music, and I found them very instructive. No, as listening experiences, they're not as good as some of the various albums on which the cuts originated. But that's not the point: They are very good ways to get an overview, to get oriented, to know where to go next. After seeing this series and studying the accompanying CDs, when I go into the music store and start perusing the jazz disks, I find that I recognize a whole lot more and can surmise a whole lot better what's what and what would interest me. For instance, tonight I saw "From Spirituals to Swing," a three CD set of Carnegie Hall jazz concerts in 1938 and 1939. A month ago, the list of personnel would have meant near-nothing to me--I probably wouldn't have even known what I was looking at, and I doubt I would have looked at the thing for more than thirty seconds. Now, though, I studied and comprehended the personnel and got all excited--"This I gotta hear." So I bought it, and it's great. Now, isn't that reason enough to recommend this series? That the overall interpretive framework of the series may need correction is not a trenchant criticism, in my opinion. To get a comprehensive understanding of anything, you have to start with *some* systematic framework, which you can then modify, maybe even refute, as you encounter further data. Logically, the first such framework you acquire has to come from someone else, unless you are a genius of extremely wide learning.No, Ken Burns' "Jazz" isn't the only guide to jazz you'll ever need--as others have noted, some of the omissions are glaring. But it's fine place to start. If you really want to get a sense of jazz, this is an excellent investment, in my opinion. Yeah, it's pricey--but cheaper than, say, an adult education course on jazz appreciation at your local community college (if you include texts and other supporting material). And if you don't want to spend the money--well, you can hint real hard to your significant other that you'd like it for your birthday or Valentine or some such thing.Postscript: I almost didn't buy this because of the characterization of Wynton Marsalis's role by several other reviewers here. I'd never much liked his music--it always seemed too cerebral, almost architectural, for my tastes--chilly, not very visceral. (That's just my personal taste--I also find most of Ella Fitzgerald--except her duo wok with Armstrong--a bit emotionally distant, unlike Sarah Vaughan or Billie Holiday or Carmen McRae or many others.) I was skeptical about any documentary that made Marsalis the central story teller. Well, two things: (1) He just isn't the central story teller here. He does not have anything approaching the majority of commentator air time. It is certainly true that he plays a role analogous to Shelby Foote's in "The Civil War"--he is a unifying presence, especially in the early going and toward the end. This is just good film making--to establish "characters" whose presence throughout helps give unity to the piece. (2) I really liked Wynton in this documentary. He came off as much earthier, more laid back, mischievous, funnier and more fun, than I ever would have imagined. And he is really quite illuminating, especially when he explains various musical concepts--like the "Big 4." (I went back and listened to "Thick in the South," thinking maybe I'd like his music more now. Nope. Still feels too thought-out, too chilly, to me. Oh, well.)"

|

![Planet Earth: The Complete BBC Series [Blu-ray]](https://nationalbookswap.com/dvd/s/23/6323/156323.jpg)