| Actor: Janos Darvas Genres: Musicals & Performing Arts Sub-Genres: Classical Studio: Euroarts Format: DVD DVD Release Date: 10/19/2004 Release Year: 2004 Run Time: 1hr 42min Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 0 Edition: Classical MPAA Rating: G (General Audience) |

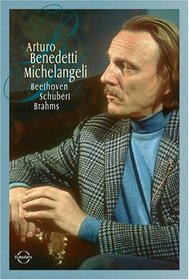

Search - Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli - Beethoven Schubert Brahms on DVD

| Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli - Beethoven Schubert Brahms Actor: Janos Darvas Genres: Musicals & Performing Arts G 2004 1hr 42min Charisma: Many great pianists, past and present, have had almost none. Others, many fewer, have had it to an almost supernatural degree. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli was one of these. The aura surrounding him, even as he ... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

|

Movie ReviewsYoung pianists can learn from this great artist. L. Chisholm | Denton, TX United States | 12/20/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "This is a great artist. No doubt about it. His playing is effortless, the sound he makes from the piano is unearthly, and music comes alive (as far a recorded performance can go). Buy this DVD! DVD This is presented in three sound formats: PCM Stereo, DD5.1, and DTS5.1. The only difference I can tell is that the DD5.1 and DTS5.1 sound more 'fuller' than the PCM, but it is only a minor difference-don't worry about sound not being excellent, because it is. Although, you may need to adjust the treble/bass on your sound system to avoid a 'rattle' on certain notes-but its not that cumbersome. It could be my sensitive system. The picture is good and in color. PERFORMACE I have to take issue with some of a previous reviewer statements. First, there is a great amount dedicated to camera shots of his hands. Any pianist hoping to learn from his technique will not be disappointed. There are shots of his face and long shots showing his peddling and posture (his posture is beautiful and calm-the supreme example of good body usage). Peddling on a piano is more a matter of how one listens to the sound, not on seeing someone's feet-there is ample opportunity on this DVD to learn his peddling technique since the nuance in sound is very good. But I would say that the majority of camera work focused exclusively on his hands. Second, my opinion is that his demeanor on stage should be an example for today's piano solo 'artists' to emulate. It has been a complaint that Michelangeli is cold, expressionless, and maybe arrogant. Perhaps this is in the eye of the beholder. Certainly, he is on stage, he plays, and then gives a slight nod to the audience as he walks out. This can often be off-putting to an audience that traveled and paid to see a great artist play. But in his defense, this can also be viewed as total humility to the music and composer. He thinks the applause and accolades should be more for the composer, not for himself or the level of artistry he has achieved. I saw him as selfless, as opposed to the mindless self-indulgence of a Evgeny Kissin, Olga Kern, or the most shockingly offensive, Lang Lang. I think to understand Michelangeli, you have to understand the goal of music is experiencing the All in the Now - to reach the eternal from the transient. He lets the music evolve through him-and this is his basic philosophy to achieving the selfless musical performance. It all depends on how the music sounds at any one given moment, not anything that is preprogrammed. Any discussion, then, of an 'interpretation' is pointless. Once one has studied and understands all of the corrolations within a composition, interpritation becomes meaningless. The music simply 'becomes,' and there is not a 'him' or an 'ego' involved. In the booklet, Sviatoslav Richter laments that Michelangeli's own standards prevents him from expressing any real love or inspiration to the work he is performing (later, Richter does say "But - one doesn't judge a master."). I would say that an artist that eschews any selfish ego in the music is displaying the ultimate in love and inspiration. Here are a couple of quotes from Michelangeli that will help those out there gain more of an understanding of his tone and general artistic philosophy from 1977: *"Very early on, I stopped listening to other pianists. I withdrew into myself and began studying on my own. to begin with, I do not like to play the piano at all. I found it far too percussive. And so, I studied the organ and the violin. Out of these studies, I found my own way of playing the piano. I discovered that the sounds made by the organ and the violin could be translated into pianistic terms. If you speak of my tone, then you must think not of the piano but of a combination of the violin and the organ." *"I do not play for others-only for myself and in the service of the composer. It makes no difference to me whether there's an audience or not. When I sit at the keyboard, I am lost. And I think of what I play, and the sound comes forth, which is a product of the mind. Today's young musicians are afraid to think. They do everything in order NOT to think. Animals are better off. At last they possess instinct. Man has lost his instincts-he has lost contact with himself. Before an artist can communicate anything, he must first face himself. He must know who he is. Only then can he dare to make music!" " The Performance is Superb; The Camerawork a Bit Less So J Scott Morrison | Middlebury VT, USA | 10/20/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "Most people agree that Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995) was one of the giants of recent pianism. I never had the honor of hearing him live, but I've treasured many of his recordings over the years. (I am particularly fond of his recording of the Ravel G Major Piano Concerto, coupled with the Rachmaninoff Fourth Concerto, on EMI.) And I have seen him only once on television--many years ago playing the Beethoven Fourth Concerto with I don't remember whom. (I've never seen the VHS/DVD that features him and Richter; I really need to rectify that omission.) So, this DVD was a welcome arrival. I certainly was not disappointed with the performances here: Beethoven's Sonata No. 11 in B Flat, Op. 22, and the Sonata No. 12 in A Flat, Op. 26; Schubert's Sonata in A Minor, D. 537 (Op. 164); Brahms's Four Ballades, Op. 10. Indeed, they are immensely enjoyable, and in some cases stupendous. Michelangeli didn't play all the Beethoven sonatas in his career, at least not in public; in fact, he only played a handful of them. And Opp. 22 and 26 figured large in his recital programs. They are played in reverse order here and I would like to spend a little time on the Op. 26 because I find it so wonderful. From the very beginning of the first movement we know we are in for something special: the sforzato chord at m. 4, for instance, has notable emphasis and slight prolongation on the D flat (which is actually a crushed appoggiatura in an otherwise straightforward A flat chord) that sets the tone for the fairly bold manner of Michelangeli's take on this movement that is so often played as fairly tame, fairly pastoral. (By the way, did you know that Op. 26 is one of only two Beethoven sonatas that do not contain a sonata-allegro movement? This first movement is an andante set of variations the beginning of each of which is here captioned discreetly on-screen.) Variation II is notable for the delicacy of Michelangeli's staccato left-hand octaves; his hand almost never leaves the keyboard and yet there is a lightness that most pianists would obtain only by leaping off the notes in order to put some air between the staccati. Listen to the expertly controlled crescendo at mm. 5-8 of Var. III followed by sforzati in the following main bass notes that exactly match the volume arrived at at the end of the crescendo, while above them the melody's volume has gone back to the original piano. This kind of attention to musical detail is the sort of thing that makes Michelangeli a kind of god to some music-lovers. Well, enough micro-dissection. I simply wanted you to get an idea of the technical aspects of this inspired music-making. One more word about this sonata. Listen to the limpid left hand scales in the second half of the first section of the Scherzo. And then the soft yet resounding chords in the Trio. Holy moley! Before I make this review much too long for anyone to read, I'll simply comment that I find the Op. 22 slightly less startlingly vivid, but still a cut above most renditions I've heard. It's a difficult sonata to pull off, especially in the second movement whose right hand melody must be simplicity itself as well as agonizingly expressive all the while; Michelangeli manages that, although there is maybe a hint of calculation here. The Schubert A Minor reminds me a good bit of that recorded by Kempff, a pianist I know he admired. However, he begins the sonata with more forcefulness than is usually heard. This soon settles, though, into a rather more thoughtful mood; there seems to be an emphasis on dynamic contrasts throughout his traversal of this work. He finishes off with the Op. 10 Brahms Ballades. Having played the first one, 'Edward,' in my youth, I was particularly struck by his incredible control of phrasing. This is a rather more controlled reading that one often hears; many pianists really emote (in the worst sense of that word) because of the gruesome subtext of the Ballade. With Michelangeli the emotion builds to the climax and resolution and it feels natural rather than acted. This is a 1981 live performance before a quiet audience in the auditorium of Radio Televisione Svizzera Di Lingua Italiana (RTSI, the Italian language Swiss radio and television network) in Lugano, Switzerland. There is no footage of Michelangeli entering the stage; it simply opens with him at the piano ready to begin. At the ends of the two halves of the recital he simply gets up and walks away, barely acknowledging the audience. I'm told this was typical of his stage manner, but it is a bit odd appearing to me. The video camera moves rather too much for my taste. I would much rather have spent a great deal more time focused on Michelangeli's hands than his rather tic-ridden facial expressions. And we almost never get to see his pedaling, a real loss because it is one the marvels of his playing. One does gasp at the silkenness and technique of his legato, the stillness of his movements, and the forcefulness of his fortissimi that seem to come out of nowhere--he certainly doesn't telegraph his punches. Still, I suppose all this camera movement has become the norm for televised musical performances and at least it never did quite become frenetic as camerawork so often does these days. The sound is quite good. I am delighted to have this DVD. It captures both the sound and the physical technique of a pianist I've admired for many years and I'm very happy for that. Scott Morrison" A PRIVATE UNIVERSE OF SOUND DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 03/24/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "This recital from 1981 consists of Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms. I have always had the feeling that Michelangeli understood Beethoven and Mozart intellectually more than by the kind of instinct he showed for Chopin, Liszt, Debussy and Ravel. There is any amount of true insight and discernment in his Beethoven, but never the sense of revelation that I get from, say, Serkin. When it comes to Schubert there is nothing else to go on besides the one sonata here; and as regards Brahms the only other piece M left us is his astounding Paganini variations. The four works here are all early productions by their respective composers - of the five Beethoven sonatas that M ever performed four were from the early period, the Schubert sonata is the first of the three he wrote in A minor, and the Brahms ballades have the opus number 10. The 61-year-old performer does not look healthy. He smoked like a chimney, and his widow's memoir of him (available on Aura.com in Italian) seems to confirm what a glance at him would suggest, namely that he didn't eat much. The hair behind his rather odd hairline is still luxuriant, and at least he didn't dye it grey at the roots. His manner is grave and abstracted, and he perspired more than his physique might lead us to expect, another point confirmed by Giuliana. He does not sit artificially still, but there is very little body movement beyond tilting his head back now and then, and the facial muscles work compulsively. Most compulsive for me was to watch those mighty fingers. Their movement verges on languid - at one point in the third Brahms ballade there is a succession of descending arpeggios and it was hard to see which fingers had even moved at all. However much his digits have to do, they seem to do it with the utmost economy of effort, and in the most powerful fortissimo the player's hands never rise far above the keyboard. In an interview he gave in 1977 M said that it was all one to him whether an audience was present or not. In fact I more than half believe this. On the one hand Giuliana tells us what agonies he went through prior to a public recital and his unparalleled track-record of cancellations tells its own story; but on the other hand there is a strong sense that the player is alone here with the music. This may be the most consummate technician of the instrument there has ever been, but there is no exhibitionism from him whatsoever. More than anything else what made M unique was his tone-production, and this recital is an absolutely riveting display of that. He takes a different approach to each of his three composers. In Beethoven, to his credit, he does not try to beautify the characteristically gawky effect of Beethoven's chords. The Schubert sonata is not much later in date, it was written for much the same kind of instrument as Beethoven had, M gives it a big-scale and vigorous reading, but the sound of the chords is different entirely and more euphonious. When it comes to the Brahms ballades, the miracles begin. I have a studio recording that he did, as I do for everything else on this disc, and I have Katchen and Gould by way of comparisons, but I never heard anything like this in my life. M starts as he means to continue with some striking pedalling at the start of the first ballade, and the crescendo at the start of the faster section has to be heard to be believed, rising to an enormous volume but with never a hint of harshness. Throughout all four ballades the variety of tone-colour, never seemingly contrived or unidiomatic, is wondrous. Chopin, where are you now? Eat your heart out, Debussy. This is - Brahms! As with the tone-colour so with the handling of the rhythm and timing, another string of jewels of perfection. In terms of interpretation, there was never any telling which way Michelangeli might go next. Nor indeed was there any way of predicting what kind of mood he might be in. This recital seems to have caught him at his best. As in his other perfomances of Beethoven's funeral march sonata, M disdains taking the opening variations at different speeds, a practice frowned on by Tovey but carried off with panache by Richter. He starts the march itself with a slightly dry and percussive tone, using a more legato effect when it next comes round, and he is aristocratically restrained over the rumble-flash effects in the trio. In the B flat sonata op 22 the main change I noticed was that he now takes a much more flowing tempo in the adagio, much the way Serkin used to do it. As always with him, all repeats are observed. He had mystique, and one senses it palpably here. I would say that nothing in this entire recital serves as any kind of benchmark for other interpreters. There are any number of equally `valid' ways of doing everything here. However music exists only in performance, no interpreter of any consequence takes any hypothetically `neutral' interpretation, and any great performance of any great music is always partly the interpreter's creation. Of all things on this earth music is the most divine, and the spark from on high can descend on players as well as on composers. What we have here is a phenomenon like no other. I don't propose to submit him to some sordid exercise of rating or comparison, I just doubt that his like will ever be heard again." A Pioneering Artist BLee | HK | 01/18/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "

Well, the other reviews have covered almost everything. So I would just briefly add that Michelangeli is not just a master of the piano but also a great artist. He is one of the very few pianists whose musical mind and playing has more to offer than just the score. While Edwin Fischer and Wilhem Kempff's playing would on and off reminds us of some serene church music, Michelangeli would remind us of some medieval court music. It is a phenomenon not to be missed by any music lover. Furthermore, when some pianists strive to make the piano sound more like an orchestra, others would rather have the piano sound just like a piano. Michelangeli, unhappy with the purcussive sound of the piano and an accomplished violinist and organist himself, chose to make it sound like a "combination of the violin and the organ". From these pieces, we can see how well he has achieved this and above all how he did it. Richter said among other things to the effect that this self-imposed standard is a shackle. Perhaps a shackle in the sense that it takes away from us a modern Lizst whom Cortot proclaimed so loud and clear. But then, we now have a wonderful alternative, and not just of Lizst but of all the musical pieces. We have his Beethoven sonatas quite different from any other pianists, particularly in sonority (more so than the DVD that grouped him with Richter). Likewise his Schubert (say if we try and compare him with either Brendel or Kempff) and above all his 4 Brahms Ballades. And lastly, it also occurs to me that his greatness does not simply come from his success in his pursuit on sonority, or a great command of the keyboard. Rather, it is a combination of all these factors with an enormous sense of music that make him so great. Well, if Picasso's cubism could be so well-received, why not his sonority? As Richter said in conclusion : "One doesn't judge a master..." " |

![Debussy: Preludes, Book 1; Chopin: Mazurkas, Op. 33 Nos. 1 & 4; Scarlatti: Sonatas Kk. 11 & Kk. 159 [DVD Video]](https://nationalbookswap.com/dvd/s/02/6202/176202.jpg)

![Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5, "Emperor" [DVD Video]](https://nationalbookswap.com/dvd/s/82/6982/186982.jpg)