| Actors: Maria Schell, François Périer, Jany Holt, Mathilde Casadesus, Florelle Director: René Clément Creators: Robert Juillard, Henri Rust, Agnès Delahaie, Jean Aurenche, Pierre Bost, Émile Zola Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama Studio: Criterion Format: DVD - Black and White,Full Screen - Subtitled DVD Release Date: 09/15/2009 Original Release Date: 01/01/2009 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/2009 Release Year: 2009 Run Time: 1hr 56min Screens: Black and White,Full Screen Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 9 MPAA Rating: Unrated Languages: French Subtitles: English |

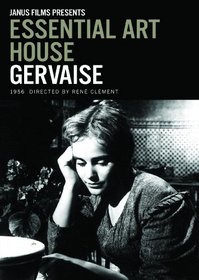

Search - Essential Art House: Gervaise on DVD

| Essential Art House Gervaise Actors: Maria Schell, François Périer, Jany Holt, Mathilde Casadesus, Florelle Director: René Clément Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama UR 2009 1hr 56min One of France's most respected directors of the postwar era, Rene Clement directed such searing psychological dramas as Forbidden Games and Purple Noon. And Gervaise, his vivid 1956 adaptation of Emile Zola's 1877 masterpi... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

|

Movie ReviewsLife in the Last Lane Tintin | Winchester, MA USA | 02/26/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "Rene Clement's Gervaise is an adaptation of Emile Zola's L'assommoir, published in 1877. Zola began, between 1971 and 1893, the long series called Les Rougon Macquart, the natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire of Napoleon III. In these novels, Zola denounced through the long history of a degenerate family, the importance of heredity, basing psychology on physiology. Gervaise Macquart is the heroine in one of these novels, L'Assommoir (1877), which examines the milieu of the working class, and the plague which is alcoholism. The series eventually comprised twenty volumes, ranging in subject from the world of peasants and workers to that of the imperial court. Zola's approach to writing novels consisted in adjusting scientific principles in the process of observing society and interpreting it in fiction, thus becoming itself a part of the scientific research. The results are carefully crafted novels, resulting in a combination of dramatic and accurate portrayals. In his treatise, Le Roman Experimental (1880), Zola manifested his faith in science and his acceptance of scientific determinism. However, Clement did not simply condense this monumental novel into a one and one-half hour film, which in the process would have only betrayed Zola's masterpiece. He made a point of preserving in their integrity certain admirable scenes, such as the brawl at the central laundry, Gervaise's dinner party, or the terrible episode of Coupeau's delirium tremens. In short, Rene Clement, while scrupulously respecting the work of Emile Zola, succeeded in making a film centered on one character, Gervaise, a poignant and incredible picture of that period. Clement's choice resulted in L'Assommoir, the novel, becoming Gervaise, the film. Obviously, Rene Clement was intimate with Zola's work. In this film, he follows Zola's naturalistic approach, which at the limit becomes a stylized realism, a vision whose blackness takes on epic proportions. Clement represents very real emotions until they are reduced almost to abstractions. The result of such representation would seem to be the very opposite of realism and of naturalism. But his cruelty, which carries him until the end of a particular situation, sometimes even too far, merges with Zola's exacerbation of the situation (although Zola's clinical details are mixed with a resonant lyricism). With Clement, we do not end up with caricatures but with an authentic naturalism, which although refined is not less cruel. Rene Clement achieved his aims by a meticulous research of the French historical period from about 1850 until 1870, a dark period indeed. Together with Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost, the other two script-writers, his research showed that the terrible truths denounced by Zola were still understated. Clement strove to achieve the proper atmosphere by researching paintings and engravings of the time. His representation of the Paris workers' section known as La goutte d'or, in the northeastern part of Paris, is done in the most realistic fashion, at least from what we now imagine it to have been through the era's literature, history, and chronicles. A first-class group of actors was assembled to breathe life into Zola's words. Maria Schell, an accomplished actress with more than eighty films on her resume, received the Volpi Cup for best actress in 1956 for her interpretation in the role of Gervaise. Francois Perier (1919 - 2002), who received the 1956 Best Foreign Actor Prize from BAFTA for his role in this film, Armand Mestral (1917 - 2000), and Susy Delair, all classical and versatile actors, belonged to a small group of actors who literally monopolized the French screens in the 1940s and 1950s. Francois Périer's career extended more than seventy years until his last film in 2002. Armand Mestral, also known as a popular singer, appeared in about sixty films, starting in the mid-1940s. Susy Delair, whose film career started in the early 1930s, was very popular until she retired in the 1980s. Rene Clement shows his virtuosity in the cutting and editing of his work. The linkages, which give his film its extraordinary wholeness of form and its fluidity, seem perfectly simple, but are actually the subtle results of an expert's work. The dissolves, when not passing directly from one scene to the next, are almost seamless, and most often they are accompanied by voice over comments. Clement exploits the lighting changes to reinforce the story. Many sequences open with a clear, pale luminosity, ending in a night-time. This, in fact, gives a kind of symbolic lighting to the film. The camera motions are primarily tracking-pan shots, with the camera constantly following the actors in occasionally long, or sometimes infinitely short, motions, but always moving. In opposition to the flexibility of these many displacements, long motionless shots reinforce the main dramatic scenes. There are numerous series of close-ups, which serve either to emphasizing the psychology of the characters, or because the overall composition of a shot has a precise psychological significance. Much of the dialogue is taken verbatim from Zola's novel. Discrete commentaries in voice over by Gervaise link certain scenes and remind us that L'Assommoir has become the history of this woman. Little by little, Gervaise's commentaries diminish in frequency with the film progression, as she becomes more and more tired and despondent, eventually disappearing completely, replaced by the sound effects. The music is by the renowned classical composer George Auric, a member of le Groupe des Six (Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honegger, Germaine Tailleferre, Francis Poulenc, Louis Durey, and Geaorge Auric). Clement's choice of Auric to write the music for this film was not arbitrary. The credo of the "Six" was a music based in everyday life, on vulgar spectacles (circuses, fairs. music halls, street songs), to confront us with the "real life." Auric's music is discreet and used sparingly. The poet and writer Raymond Queneau, one of the founders of the surrealist movement, wrote the words of the Song of Gervaise, which includes in a symbolic form all of Gervaise's psychology. At the time Zola wrote the novel, he was strongly criticized for using such powerful material, as well as for presenting opinions of the lower classes. Gervaise is above all an historical document of the life in the middle 1850s, in the working class milieu in Paris. The daily, unbearable workers' conditions are remarkably well-portrayed in this film, without editorial comments. In those days, a work-day for a man, woman, and child was 15-18 hours; strikes were practically unknown and when one happened, it was violently repressed and their leaders severely punished. There were no social security or retirement plans, and aging without children to help in old age was literally an early death sentence. The salaries were extremely low, and an accident or a sickness would irremediably throw a family into dire, abject poverty. There was no escaping from this reality. The only form of entertainment other than an occasional visit to a Caf'conc (Cafe Concert), a kind of musical show, was l'assommoir (a bludgeon), the term for a low-class tavern, where men and women were easy prey to alcoholism. Clément shows us the irremediable descent of Coupeau into the alcoholic hell, and all the consequences to his loved ones. Soon after, Gervaise will follow. Rene Clement tells us the story of Gervaise, a woman subjugated by the men she loved, captive of society, her social background, and social condition, who tries to escape her proletariat status. But external and internal conditions frame our lives, against which our will has no control, and Gervaise's revolt against her condition, her desire to possess her own shop, rising above her station, may have also brought her downfall. A Hindu person would say the she violated her dharma. But who knows? Maybe she would have ended up in the same place, but at least she got the satisfaction of having chosen her own instrument of torture. One of the three important men in Gervaise's life is Goujet, and with him Clement introduces a sub-theme--a political one. The 1850s saw the democratic ideals of the first French revolution of 1789 logically progressing toward a budding Socialism, coming in as a reaction against the new slavery of the industrial revolution, Capitalism. Goujet, the blacksmith, represents the ideal socialist revolutionary, a hard-working, honest laborer, just asking for justice and his deserved place "at the table." He is ready to sacrifice himself for the benefit of a better life not only for himself, but also for his fellow workers. Rene Clement's adaptation of Emile Zola's novel L'Assommoir is widely regarded as one of his best films and it is unquestionably one of his most poignant and intense works. Although you may encounter some difficulties in getting your hands on this video, your efforts will certainly be rewarded " AN UNFORGETTABLE MASTERPIECE Peter Fraser | Sydney, NSW Australia | 10/14/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "I was only 12 years old when I saw this film in 1957 in New Zealand and at that tender age rated it as one of the very best films that I had ever seen.Seeing it on television several times in recent years has not diminished my feelings in calling this an unforgettable masterpiece.This is one of those rare classics that still lingers in the mind fifty years later." Exceptional film! Hiram Gomez Pardo | Valencia, Venezuela | 08/10/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "Splendid and vivid adaptation of Zola's play. Emile Zola was the real father of the French realism, his literary style is extremely reiterative about the minuscule insights in the human soul. He focuses on the tribulations and little triumphs and defeats of the middle class and poor families in a French in transient process toward the Industrial Revolution. In certain way he is the counterpart of Charles Dickens in France, despite he is less optimist. A woman makes the best she can, struggling and fighting against the odds till finally she gives up and succumbs to tawdry life of his drunk man.

Another triumph of Rene Clement! Why hasn't it been released on DVD format? A supreme riddle. " |