| Actors: Toni Ceo, Jim Coursar, Paul Elliot, Nick Kleinholz III, Gabe Lewis Directors: Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr., Robert J. Emery Creators: Robert J. Emery, Jean Yeaworth, John Gimenez, John Pappas, Rudy Nelson, Shirley Nelson Genres: Horror, Musicals & Performing Arts, Mystery & Suspense Sub-Genres: Horror, Musicals, Mystery & Suspense Studio: Image Entertainment Format: DVD - Black and White,Full Screen DVD Release Date: 11/02/2004 Release Year: 2004 Run Time: 3hr 10min Screens: Black and White,Full Screen Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 6 Edition: Special Edition MPAA Rating: Unrated Languages: English |

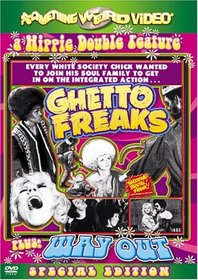

Search - Ghetto Freaks/Way Out on DVD

| Ghetto Freaks/Way Out Actors: Toni Ceo, Jim Coursar, Paul Elliot, Nick Kleinholz III, Gabe Lewis Directors: Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr., Robert J. Emery Genres: Horror, Musicals & Performing Arts, Mystery & Suspense UR 2004 3hr 10min Hanging out at a late-sixties rock club, stoner-freak Sonny watches as a wealthy mother tries to "rescue" her daughter from the corrupting hippie environment. Acting quickly, Sonny slips the girl the address of his nearby ... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsA fantastic double-feature time capsule Brian T | Canada | 07/31/2009 (4 out of 5 stars) "Something Weird's typically garish sleeve design and sensationalistic copy don't really do these two topical films justice. In fact, in the case of WAY OUT (1967), based on a stage play by reformed junkie John Giminez (who also plays a role in the film), it would seem history itself has also not done the film justice, consigning it to the dustbin of reformed junkie pictures until Something Weird rescued it from an undeserved oblivion.

Though ostensibly the second feature on Something Weird's double bill, WAY OUT is actually the more important film cinematically and perhaps historically, utilizing as it does a largely Puerto Rican cast of real-life former heroin addicts who, surprisingly, are extremely capable performers. Their experiences clearly inform the characters they play, and while we're only given small hints about the kind of socio-economic conditions that might lead a young man (or woman) to start mainlining (the dingy New York boroughs in which the film was shot are a fairly obvious visual clue), we're spared no grisly detail of the chronic addiction cycle experienced by them once they do, and the lives and families they often destroy. This is a film that would probably stand up to inclusion in the Criterion Collection, not so much for what it "says" (heroin is bad; nothing new there) but for how it dared to say it with an amateur cast in 1966, a time when most exploitation pictures dealing with drugs adopted one of two crackpot philosophies: a) junkies and hippies are evil and only the law, the government or the church can stop them (in films made by conservatives); or b) junkies and hippies are pacifist heroes, screwed over by the law, the government, the clergy or all three (films made by liberals). WAY OUT has no such agenda beyond illustrating in often graphic detail the day-to-day existence of the addict, the circle of lowlifes he must traverse in search of another elusive "fix", and the people he hurts on his way down. This is raw meat for 1966, often downright painful to watch and never preachy until the heartfelt coda where the performers all break character, confess that Jesus saved them, and march down the street in unison belting out a gospel tune! Yes, this is, at its heart, a Christian film, though one probably made more with neighborhood rehabilitation clinics and missions in mind than grindhouses or drive-ins or even churches. Where "churchy" pictures, then as now, tended to be downright laughable in their conservative moralizing and wrongheaded portrayals of sinners of all imaginable stripes, WAY OUT doesn't look down on its lost souls. It simply shows you how they live, the bleak, almost microcosmic worldview they embrace, how they hurt, and how difficult it really is to break the vicious cycle. Remove the invitation to Christ from the last five minutes and this is still a harrowing journey, and the fact that it's not enacted by a cast of famous Hollywood method actors slumming for awards makes it all the more believable. Though director Irwin S. Yeaworth (better known for THE BLOB and the 4-D MAN, but a Christian filmmaker before and after his dalliances with sci-fi) is no longer with us, many in the cast and crew still are, as is Yeaworth's wife Jean, who served as co-writer and music supervisor on the picture, which makes one pine for some kind of audio commentary that would enlighten us about the production of what it probably the first realistic anti-drug picture to headline an ethnic minority cast. The other film in this two-fer is GHETTO FREAKS, retitled from the original LOVE COMMUNE and SIGN OF AQUARIUS after some clever distributor inserted an incongruous two-minute sequence of a black shaman leading a bizarre love cult ritual. Surrounding that dopey sequence is the episodic tale of a group of hippie pals protesting, panhandling, consuming and loving their way through an ugly Cleveland winter while sharing a run-down pad. Into their free-for-all comes a sweet young thing from the suburbs who doesn't take long to dig their vibe, imbibe their goodies and get it on with their leader (Paul Elliot). Along the way they're hassled by the police for unlawful public assembly, and frowned upon and argued with by Cleveland's blue collar conservative element that wishes they'd just get jobs, haircuts and baths. Eventually, Elliot's former drug dealer bosses squeeze him to rejoin the circuit, and his refusal leads to tragedy, placing GHETTO FREAKS squarely in the second philosophical category of drug films I mentioned above: the hippie stoner as harmless hero, bullied by society above and the "real" vermin below. More a series of vignettes than a cohesive plot, GHETTO FREAKS moves like molasses - most sequences run longer than necessary, but two of them are verite gold: one sees the cast panhandling FOR REAL on the streets of Cleveland, recorded covertly from some distance away; the other sees them debating their very existence with an arguably "real" working class stiff in a public square, filmed both from afar and by a "news camera" flitting about the crowd. As with nearly every other sequence in the film, both of these doses of realism overstay their welcome in hindsight, but their fascinating time capsules while they play out. Something Weird goes a little light on the extras this time around, with five sensationalistic trailers for other junkie films of the period and a short classroom scare film, in color, called NARCOTICS: THE INSIDE STORY, which explains the dangers of drugs and exalts the virtues of being young, white, beautiful and frolicking on the beach. Good times." |