| Actors: Emmanuel Schotté, Séverine Caneele, Philippe Tullier, Ghislain Ghesquère, Ginette Allegre Director: Bruno Dumont Creators: Yves Cape, Bruno Dumont, Guy Lecorne, Jean Bréhat, Rachid Bouchareb Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense Studio: Fox Lorber Format: DVD - Color,Widescreen - Subtitled DVD Release Date: 02/13/2001 Original Release Date: 01/01/2000 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/2000 Release Year: 2001 Run Time: 2hr 28min Screens: Color,Widescreen Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 4 MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Languages: English, French Subtitles: English |

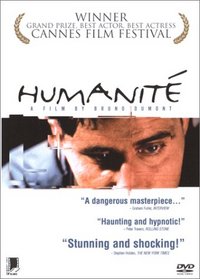

Search - Humanité on DVD

| Humanit Actors: Emmanuel Schotté, Séverine Caneele, Philippe Tullier, Ghislain Ghesquère, Ginette Allegre Director: Bruno Dumont Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense NR 2001 2hr 28min Bruno Dumont?s (The Life of Jesus) controversial and award-winning film follows a police detective trying to solve a brutal rape and murder of an 11 year-old girl. |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsFor adults only 02/01/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "This is one of those unusual films that despite its snail's pace is thoroughly gripping and, in two or three instances, shocking. The image of the raped child is disturbing, to say the least; and the sexuality is explicit. Why is this film so fascinating? It's about 2 hours and 20 minutes long, but I didn't want it to end. Once you see it, it's going to take a while to shake it off. It's so real and unpretentious that it's almost frightening. If you can stomach graphic nudity in closeup, and have the patience to sit through the first half hour, the rest is a psychological experience you won't soon forget. "Humanite" is what I would call the epitome of the "anti-Hollywood" style of filmmaking. Brilliant!" A World Beyond Words mackjay | Cambridge, MA | 04/20/2001 (4 out of 5 stars) ""L'Humanité" is a fine example of a film that takes some time to absorb. This is to say, not just the amount of time it takes to watch the 2 and one-half hour film, but the time required afterwards for contemplation. The style and pacing of Bruno Dumont's film are so striking that the viewer needs some distance to sort out what has been experienced. Most closely resembling that of Michelangelo Antonioni, the style of "L'Humanité" consists of long takes, occasional slow pans and sparse dialogue. As with the great Italian director, characters here seem to live on the surface of some undiscovered emotional realm. They seem to grope constantly, at a loss for words, for something that lies beneath. In an interview, Dumont has said that he wrote the leading role of Pharaon after meeting the actor Emmanuel Schotte. A previous conception of the screenplay was rejected and Dumont fashioned the character upon the first-time actor's real personality. This is a case of an actor really being exactly like the part he plays. In fact, Dumont chose all amateurs to play in this film because he did not want associations made with name actors. This possibly explains the striking truthfulness of the three central performances.Dumont sets up, in this film, a kind of laboratory situation. The viewer is confronted with a seemingly enigmatic main character. At first it may be wondered if a connection should be made between Pharaon and the rape/murder is investigating. There is a connection, but not the most obvious one. We are made, at several points, to experience Pharaon's RESPONSE to the act of this murder: most often an inarticulate scream. Pharaon is chosen as the main focus because of his own history: some time in the past he had, and lost, a wife and child of his own. This combination of facts and events sends Pharaon on a kind of internal odyssey. He is desperate to find some understanding of what has happened. What makes the film so interesting , and so deeply cinematic, is that this understanding cannot be verbal. Pharaon is not a verbal personality. Over and over again, he attempts and gains communication through touch, sometimes in surprising ways. In this important sense he is contrasted with the other characters in the film. His friend Domino only understands communication through touch as well, but her pathway must be sexual. In several scenes, she and her handsome lover Joseph sit or stand in silence, in a gray landscape or a drab cafe. Only in the sex act itself do they seem to achieve real communication. As for Joseph, repressed anger at his mundane existence leads to vitriolic outbursts of violence. All three characters are painfully frustrated in their need to circumvent the word for the act.The feature of Dumont's technique in this film that will stay with most viewers-and that will infuriate many-is its very slow pace. There is a deliberation in this film that is, again, comparable to Antonioni or to Tarkovsky. Yet, there is something new here. At this lugubrious tempo, the viewer is made to experience the world of this small, dull town in its maddeningly quotidian fullness. In sum, "L'Humanité" is a very close observation of humans and their behavior in the world. Through the eyes of Pharaon (a character, by the way, shown to be a descendant of a famous late-19th Century French portrait painter) humanity is observed. And, in the film's final embrace, there comes perhaps not understanding, but compassion." So close and so faraway from perfect at once Jonathan Rimorin | Cormorant Island | 02/28/2002 (4 out of 5 stars) "Pharoan de Wilder, the police superintendant of a small French city between Lille and Paris and protagonist in Dumont's "L'humanité," is far, far from the gruff detectives encountered in policiers and film noir. In his blank unblinking face and in his childlike padding through his investigation and life are family resemblances to the characters living in Bresson's movies, masterpieces of no action and less reaction. De Wilder, however, may also be related in some fashion to his titular compatriot, the late Inspector Clouseau. Clouseau's cousin in a Bressonian film? The juxtaposition is facetious, and while watching the first revelatory and masterful half of this film, you would think such glibness on my part not only, well, glib, but outright barbaric. De Winter is investigating the murder of an 11-year-old girl in his small town; he is also little advanced beyond the mentality of an 11-year-old child himself. He lives with his mother, is devoted to his bicycle and his rose garden, and spends almost the whole of the movie in wide-eyed, half-confused regard of the world about him. He is drawn to animals and to the sun and limits himself to functional speech, often walking away in the middle of a conversation to stare out the window. In short, he is a complete cypher, unilluminated by the few details we are given (his girlfriend or wife and his child were killed or misplaced two years earlier; he served some time in the military; he ... at the keyboard) and thus perfect to project our own wants, desires, feelings and dreams upon. For me, de Wilder strikes me as one of Dostoevski's holy-fools or the lamed-vovniks in Jewish legend, an innocent so in sympathy with the world's pain that he must run screaming into some desolation, and yet so resonant with the world's beauty that he blooms with his roses. I think it interesting that [others find] De Wilder's blankness "a symptom of his" [the character's?] "rage and self-hatred," and interpret those two beautiful, mysterious scenes as signs of psychosis.The film's other two main characters are Domino, a young woman who lives a few doors down from De Wilder and his mother, and to whom De Wilder is devoted, and Joseph, a bus driver whose hobbies are ... Domino and insulting everyone else. They are predicated entirely on their wanton hungers, and like every other character (the chief constable's relentless interrogation of the children, the curator preparing his exhibit, the rabblerousers at the restaurant) seem obsessed or driven to fulfil some appetite like everyone else. And this is humanity. ... the first half of the movie suggests these themes with beautiful and often startling imagery, fluid editing, with not a single jarring shot or reverse-take, and its actors deliver vivid performances (watch the frightening play of emotions dance in De Wilder's eyes as he says, "I do not wish to talk about it" and attempts a smile). And it is frustrating and heartbreaking to see these same ingredients continue admirably in the film's second half, where De Wilder seems to be spontaneously endowed with the superpower of smelling guilt (or maybe it's smelling fear? or maybe it's a spontaneous attraction towards gyus' necks? He was checking out the inspector's neck for a long time, hmmm...) culminating in the ability to suck mortal sin by use of deep soul-kissing. Maybe Bruno Daumont intended to shatter the contemplative reverie made so beautifully in the first half of his movie with such slapstick; or, worse, he didn't consider that his audience might find his deep Guilt-Is-Stinky scene pretentiuosly funny. Or maybe we Americans are estupide, maybe that's it.The last insult added to the injury is how the initial shocking image of the film ... -- actionable, amoral, should be illegal to put on film, and yet an effective slash into the viewer of the monstrous enormity of the crime committed -- that image is made part of a rhetorical trope and visual leitmotif that substantially diminishes that image's shocking impact and its singular force. ..." A year later, I'm still affected by this film Jonathan Rimorin | 05/23/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "Imagine for a moment that you're a cop in a small town out in the middle of nowhere where NOTHING ever happens. In addition, you live a dull, conservative life with your widowed mother. You have only 2 friends (not close ones) one of which you're in love with but can never fulfill it. Now... suppose a shocking "big city" murder did happen and it was your sole responsibility to find out who did it. You have very little clues, no support and no one that you feel comfortable enough to confide in. That would be pretty frustrating right? It would obsess your conscience 24/7 and affect what little social skills you have already. That is the very thing that makes L'Humanite work!!! This is a film based on one frustrated man's efforts to solve an evil crime. Its long, exhaustive and at times frustrating JUST LIKE THE CASE WOULD BE IN REAL LIFE. I commend Bruno Dumont for creating something so non-spectacular and believable. The world has had its fill of Bruce Willis shoot-em-up cop movies. I saw this film last year after it deservedly won the Grand Prize at Cannes. The fact that a whole year later, I'm still moved by what I saw, makes L'Humanite a 5-star film."

|

![Fences [DVD]](https://nationalbookswap.com/dvd/s/25/3925/323925.jpg)