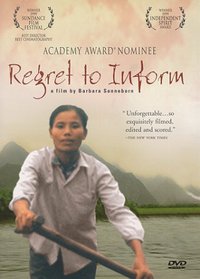

| Directors: Xuan Ngoc Nguyen, Lucy Massie Phenix, Ken Schneider Genres: Educational, Documentary, Military & War Sub-Genres: Educational, Military & War, Military & War, Military & War Studio: Docurama Format: DVD - Color DVD Release Date: 05/02/2000 Original Release Date: 01/01/1998 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/1998 Release Year: 2000 Run Time: 1hr 12min Screens: Color Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 1 MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Languages: English |

Search - Regret to Inform on DVD

| Regret to Inform Directors: Xuan Ngoc Nguyen, Lucy Massie Phenix, Ken Schneider Genres: Educational, Documentary, Military & War NR 2000 1hr 12min On January 1, 1968, Barbara Sonneborn?s husband, Jeff Gurvitz, left to fight in Vietnam. Eight weeks later, on February 29, 1968, he crawled out of a foxhole during a mortar attack to rescue his radio operator and was kil... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsSlanted perspectives gained through emotional manipulation Andrew Lam | 08/19/2005 (2 out of 5 stars) "As a longtime but wary viewer of Vietnam War flicks, I've learned that to be moved by a piece of work is not necessarily the same as to be illuminated by it. This is true of the documentary "Regret to Inform," about Vietnam War widows, by Barbara Sonneborn. While I was moved to tears by parts of the film, I found little that jibed with my own Vietnamese memory: that of a country deeply divided by a civil war, where North and South were at each other's throats long before the Americans arrived. My eldest uncle joined Ho Chi Minh's army in the North while his two brothers joined the South, later becoming pilots who dropped B-52 bombs on him and his troops. It is a memory of Vietnamese killing Vietnamese in a bloody and senseless theater where Americans were mere side actors. That America plays the central role in Sonneborn's documentary is no surprise. After all, Vietnam was a complicated, three-sided war, a difficult narrative that often gets reduced to two sides - America vs. all Vietnamese. From that perspective, we see Americans as perpetrators of violence and Vietnamese as innocents in conical hats, waiting to be murdered. We are told this not so much in words but in the footage of American planes dropping bombs and napalm onto the tropical landscape. We are shown Vietnamese being herded and tied up like oxen by GIs or beaten by the butts of M-16s. Not once do we see a Vietnamese holding a gun. Not once do we see a Vietnamese in army uniform. Only Americans have that privilege, as GIs, as wielders of history. Vietnamese, so the images suggest, were passive victims of their fate - which does not explain America's defeat. What I want to tell Sonneborn and all American filmmakers is this: Vietnam is not 14 years old. Vietnam's story does not begin when the first American helicopter landed in the rice fields, and it does not end when the last helicopter left the rooftop of the American Embassy in Saigon. In the 20th century alone, Vietnamese fought, besides their countrymen, the French, the Japanese and the Chinese, and then went on to occupy Cambodia for 10 years. They never lost a war - not counting South Vietnam's defeat. "What is the legacy of war?" Sonneborn asks in her film, "and what happens after the troops go home?" What happened is that Hanoi - America's victim-turned-victor - immediately enforced a vindictive policy in the defeated South, putting nearly a million men in "re-education" camps and forcing hundreds of thousands of families to survive in malaria-infested New Economic Zones while confiscating their properties. More than 2 million Vietnamese risked death at sea as boat people to escape. Where, I wonder, are the voices of the widows whose husbands starved to death in re-education camps? Where are the voices of those who ended up in refugee camps waiting to be accepted by the West? Why, I wonder, is it easier for filmmakers to fly thousands of miles across the ocean to Hanoi to interview communist officials and film scenes of exotic limestone mountains or sparkling rivers than it is to drive a few miles to San Jose or Los Angeles or Dallas to interview the million or so Vietnamese-Americans? Is it because their epic story might somehow dislodge Americans' own narcissistic sense of guilt? If that is the case, the answer to Sonneborn's question regarding the legacy of war is this: War and its aftermath are always bad, but it is worse when its history is simplified and its many voices muffled. The result of such misinformation is always ignorance. " Looking back with tears in our eyes Dennis Littrell | SoCal | 12/02/2001 (4 out of 5 stars) "Some have called this documentary "propaganda," and I can understand that point of view since there is no mention of Viet Cong atrocities here; but since this was made some thirty years after the war was over, it can hardly be propaganda. It does present a limited point of view, that of the women who suffered because of the war, but that was film maker Barbara Sonneborn's intention. She wanted to show how she personally suffered because she lost her husband in the war and how she has come to grips with that loss, but more than that she wanted to show how other women also suffered and what the war meant to them, including, and perhaps especially, the Vietnamese women. After all, it was their homes that were bombed, not ours.Imbedded within and at the heart of Sonneborn's reflections is the story of Xuan Ngoc Nguyen, the Vietnamese-American woman who served as her translator. Nguyen tells her personal story beginning with the sight of the bombs falling on her village and that of her five-year-old cousin being shot by an America soldier (who became horrified at what he had done). She tells of her stint as a prostitute for G.I.'s, her marriage to an American soldier and her coming to America, the end of her marriage, and the implications of her life afterwards, raising her son and becoming Americanized, and finally her return with Sonneborn to the country of her birth. She is the heroine of this film, a woman who faced the horrors of war, did what she felt she had to do, somehow survived in one piece, and now looks back with tears in her eyes.Sonneborn's documentary owes part of its effectiveness to the contrast between the black and white and fading colored film shot during the war and the brilliant rush of greenery so beautifully photographed today. The effect of seeing the verdant fields of today's Vietnam contrasted with a land torn apart by bombs and sickened with Agent Orange is to show that despite all the damage and death of the war, the fields and those who tend the fields, recover. In this sense--and John Hersey used the same idea in his book, Hiroshima (1946), when he described how the grass grew back after the atom bomb--the futility of war is demonstrated. We kill one another with a ferocious abandonment; nonetheless, the greenery returns, even if, as Carl Sandburg implies in his poem, "Grass," it is fertilized by our blood.Consequently this film cannot but play as an indictment of the war in Vietnam, and for some, as an indictment of all wars. I will not argue with that. As anyone who has really thought long and hard about war knows, from Sun Tzu to General Powell, it is always best to avoid the war if that is possible, but there comes a time and a circumstance in which one has no choice. The jury has long since rendered its verdict on the war in Vietnam. We are reminded of that every time we hear a commentator say, "We don't want another Vietnam." But there is an enormous difference between the horrendous stupidity of our involvement in Vietnam and the absolute necessity of defending ourselves against the aggression of the fascists and imperialists during World War II. And the war being fought today against terrorism is also one that cannot be avoided. I see Sonneborn's film as a reminder not only of the horror of war, but of our responsibility to be sure that our cause, as Bush has it, "is just" and our methods restricted to the task at hand, and that the suffering of those involved be ended as soon as humanly possible." Some woud rather forget, but his film remembers... Linda Linguvic | New York City | 02/24/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "Nominated for an Oscar in 1999 and winner of best documentary and best cinematography at Sundance, this little film is tremendously intense. Twenty years after her husband was killed in Vietnam, filmmaker Barbara Sonneborn interviewed more than 200 American and Vietnamese women widowed by the war. She traveled to Vietnam to interview the Vietnamese widows and the scenes in Vietnam are haunting with their magnificent cinematography and graphic stories as told by the women. In between the interviews, and sometimes in the background, she uses rare archival footage to reinforce the individual stories.The American women are living with the memories long after their husbands' deaths, wondering about what happened over there. There's a woman who wishes she had the nerve to smash her husband's hand to keep him from going, a woman whose husband wasn't killed in Vietnam, but came home sick with multiple cancers from Agent Orange, a Native American woman whose husband, a former rodeo rider, felt a racial connection to the Vietnamese people. Most of all though, it was the Vietnamese women whose stories were the most moving. After all, the war took place on their land. They also lost children and parents and had their homes burned down. Some of them were tortured and all of them have memories of murder and destruction. It is all so very very sad.Yes, this is an anti-war film, produced many years after the Vietnam war, at a time when people would rather forget. But for those whose lives were forever altered, there is no forgetting. This film remembers." Oscar nominee and sundance winner, an excellent portrait Larry Mark | nyc | 04/12/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "An Oscar nominee, Sundance 99 winner, and Golden Spire winner. On January 1, 1968, Barbara Sonneborn's husband, Jeff Gurvitz, left to fight in the Vietnam War. Eight weeks later, on February 29, 1968, he crawled out of a foxhole during a mortar attack to rescue his radio operator and was killed. Sonneborn learned of her husband's death on her 24th birthday. "We regret to inform you..." read the official notice. When his personal effects were returned three months later, his dog tags and wedding ring were encrusted with his own blood. The shock and grief eased with the years, but not the anger. On January 1, 1988, twenty years after Jeff's death, Sonneborn woke up suddenly determined to do something about his death in the Vietnam War. She began to write Jeff a heart wrenching letter to tell him the impact that his death had on her life. She recalls the night before he left, writing, "You were so alive, so filled, filled with life... How could you not come back?" This on-going letter is the narrative thread of Regret to Inform. In all those years Sonneborn had met only one other Vietnam War widow. She knew that she wanted to find other widows on both sides of the conflict, to understand how their husbands' deaths had shaped their lives. What could be learned from these women's stories about war, loss, survival and healing after all these years? Sonneborn knew she had to go to Vietnam to find the place where her husband was killed, and to talk to other widows. Her documentary film Regret to Inform is both her response to her experience and the agent of her catharsis. Sonneborn interviewed over 200 widowed women by phone and in short pre-production interviews, and another 43 in person, 25 of these in Vietnam. Widows include Norma Banks, April Burns, Le Thi Ngot, Charlotte Begay, Nguyen Thi Hong, Diane Can Renselaar, Tran Nghia, Lula Bia, Grace Castillo, Phan Thi Thuan, Phan Ngoc Dung, Truong Thi Le, Thurong Thi Le, Truong Thi Huoc, Nguyen My Hein, and Nguyen Ngoc Xuan."

|