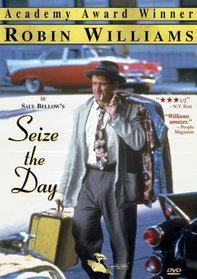

| Actors: Robin Williams, Richard B. Shull, David Bickford, Glenne Headly, Stephen Strimpell Director: Fielder Cook Creators: Eric Van Haren Noman, Sidney Katz, Brian Benlifer, Chiz Schultz, Robert Geller, Ronald Ribman, Saul Bellow Genres: Drama, Television Sub-Genres: Drama, Television Studio: MONTEREY VIDEO Format: DVD - Color DVD Release Date: 02/18/2003 Original Release Date: 01/01/1993 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/1993 Release Year: 2003 Run Time: 1hr 33min Screens: Color Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 3 MPAA Rating: Unrated Languages: English |

Search - Seize the Day on DVD

| Seize the Day Actors: Robin Williams, Richard B. Shull, David Bickford, Glenne Headly, Stephen Strimpell Director: Fielder Cook Genres: Drama, Television UR 2003 1hr 33min Studio: Monterey Home Video Release Date: 02/18/2003 Run time: 93 minutes Rating: Nr |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsA classic of American literature Lesley Freitas | Chicago, IL USA | 06/23/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "I picked up "Seize The Day" when, one afternoon, I realized I'd never read anything by Saul Bellow. Throughout high school and college, none of his books had ever been assigned to me, and though I knew his name, it never resonated with me the way the names Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, or Steinbeck had. After reading "Seize the Day," I am rather angry at my high school teachers and college professors--and myself!--for keeping me from this author for so long. "Seize The Day" tells the story of one day in the life of Tommy Wilhelm, a middle-aged failed actor who now lives in the same New York hotel as his father. Tommy is separated from his wife, and rarely sees his children; furthermore, he has been unemployed for several months, and faces losing the last of his money in an ill-conceived stock market venture. It is with all of this in mind that Tommy finally comes to a day of realization and reckoning, when he realizes his isolation and his failure. The theme of man's isolation is strong throughout the book, yet it is not what struck me most about Tommy's situation. I read "Seize The Day" immediately after finishing "The Fountainhead," and perhaps that skewed my focus a bit. What I found most interesting about Tommy is his inability to judge himself. He is aware of his failures, but cannot take the final step and truly confront them; he must ask those around him, particularly his father, both for a kind word and for a way to understand himself. I have to wonder if Tommy's isolation would be less of a burden if he weren't also isolated from himself--a thought which struck me to the core. If you are like me, and have read dozens of American classics without touching a Saul Bellow book, read "Seize The Day" as soon as possible. Bellow's style of writing and his way of getting inside of Tommy's mind is recognizably American, yet incredibly distinctive; I would venture that you can't fully understand American literature until you've read Saul Bellow." A short novel, representative of Bellow's work Dennis Littrell | SoCal | 11/23/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) ""Seize the day, put no trust in the morrow" is what Horace wrote at the end of his first book of Odes a couple of thousand years ago. And ever since, youth has been urged to make hay while the sun shines since the bird of time is on the wing--to toss in a couple more homilies. But what Saul Bellow has in mind here is entirely ironic since his sad protagonist, Tommy Wilhelm Adler has never seized the day at all, much to his unfeeling father's disgust. This then is a tale of failure (one of Bellow's recurring themes) and the shame and self-loathing that failure may bring; and yet there is a sense, or at least a hint--not of redemption of course--but of acceptance and understanding at the end of this short existential novel by the Nobel Prize winner. The way that Bellow's drowning, existential man experiences the funeral as this novel ends is the way we should all experience a funeral, that is, with the certain knowledge that the man lying dead in the coffin is, or will be, us. And we should cry copious tears and a great shudder should seize us and we should sob as before God with the full realization that our day too will come, and sooner than we think--which is what big, blond-haired, handsome Jewish "Wilkie" Adler does. And in that realization we know that he has seen the truth and we along with him. An existential truth of course. The structure of the novel, like James Joyce's Ulysses, begins and ends in the same day. Through flashbacks from Adler's nagging consciousness, the failures and disappointments of his life are recalled. When he was just a young man he foolishly thought because of his good looks and the assurance of a bogus talent scout that he might become a Hollywood star; and so he spurned college and instead went to the boulevard of broken dreams as it runs toward Santa Monica. And so began the failure and dissolution of his life. As Bellow tells it, Wilhelm has slipped and fallen into something like a watery abyss. He can't catch his breath. He is drowning. He reaches out to his father, who turns away from him. He reaches out to Dr. Tamkin, the mysterious stranger, the clever fox of a man who swindles him and then disappears into the crowd of the great metropolis. He reaches out to his wife, who will also not extend a helping hand. Meanwhile, the waters about him have grown, and he is lost. We are all lost, more or less, except those who delude themselves, who have their various schemes and delusions to distract them, is what Bellow seems to be saying. Those of us who have not seized the day, a day that is fleeting and subtle, indefinite and hard to grasp, become so much water-logged driftwood. With resemblances to Albert Camus' The Stranger and Arthur Miller's Willy Loman, Bellow's Wilhelm is the essence of the anti-hero, literature's dominate strain of the mid-twentieth century. Such men have no firm or deep beliefs. They exist for the day, like butterflies, tossed about by circumstance all the while wondering why, but without any ability to rise above their predicament, a predicament that is so ordinary, so banal, so patently unheroic to be that of Everyman. And what is the answer? For Bellow and Camus and Miller, the answer is the finality of death. A man lives, goes about craving--"I labor, I spend, I strive, I design, I love, I cling, I uphold, I give way, I envy, I long, I scorn, I die, I hide, I want"--and for what and because of what? Like the tentmaker, Omar Khayyam, we wander willy-nilly without a clue, and then become so much dust in the wind. For life IS a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying in the end, nothing. All our labors are like those of Sisyphus pushing the stone up the hill only to watch it roll back down again. We cannot help but feel in reading this novel both a sense of empathy for the man who has failed, but at the same time, we might feel like his father and want to give him a kick and say, "Wilkie, get a grip on yourself. Quit making the same mistakes over and over again." But we know that for Wilhelm it is already too late. He cannot change his nature anymore than the leopard can change its spots. We sense the great hand of fate upon him, and we shudder. For in some respects--different respects of course--we could be him. And we straighten up our frame, we return to our duties and responsibilities, to our work and the rhythms of our lives secure in the knowledge that we are stronger that Wilhelm, that although the waves may toss us about, we will not sink. At least not yet. In reading this for the first time now half a century after it was written, I am struck with how different the zeitgeist is today. We have wildly successful heroes and larger-than-life murderous villains, and nowhere is there the existential man. This short work is a splendid representative of one of my favorite genres, the short, sharply focused American novel from the early or middle 20th century. Other--widely differing--examples are John O'Hara's Appointment in Samarra, Nathanael West's Miss Lonely Hearts, F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, John Steinbeck's Cannery Row and Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea, to name a few." Seize the Day not an option for some A. Bayes | Tempe, Arizona | 11/27/1999 (5 out of 5 stars) "In one of Bellow's best works, Seize the Day tackles many of the hardships faced in the capitalistic society of America. The main character, Wilhelm, has failed miserably at virtually everything he has ever attempted. This failure is a derivation from the fact that his father has never been able to show him love. Thus, Wilhelm accepts love from anyone who is offering, and constantly gets taken advantage of by those he trusts. Hidden within the text, is the issue of the Holocaust, and how the world must reflect and look at the sins of the past in order to progress into the future. Ironically, "Seizing the Day" is not the answer for Wilhelm, or the world. From this novella, we must realize that in order to move on with our lives, we must reflect upon and accept our sins and mistakes of the past. Very powerful and moving, this novella should force every reader to think about the direction of their lives, and the importance of love and compassion." Story of modern despair and spiritual renewal immortal pickwick | Boston, MA USA | 11/22/2004 (4 out of 5 stars) "This is a powerful page-turner which in my view should be read once through to fully experience its sweeping crescendo and then again at a more deliberate pace to appreciate the beatifully descriptive langauge and symbolism of the text. Bellow writes with a detached sympathy for his unfortunate hero, Tommy Wilhelm, who finds himself on the brink of financial ruin and spiritual collapse. I think this is an important story about alienation in our modern commercial society and renewal through acquaintance with the true bared self within us that we are taught to neglect and long to return to. In just over a hundred pages, Saul Bellow manages to bring the ominously swelling pressures of his tragic hero's surroundings and inner monologue to a swirling climax, compassionately cleansing Tommy in an emotional acceptance of himself in the turbulent end. All the while, Bellow meticulously develops a suffocating world in which with Tommy we can't help but feel the merciless chaos surrounding him and amidst it all sympathize with the poignant alienation of a reflective mind. Very interesting read and highly recommended as a primer to Bellow's oeuvre."

|