| Actors: Manfred Jung, Heinz Zednik, Donald McIntyre, Hermann Becht, Fritz Hübner Director: Brian Large Creators: Peter Czegley, Richard Wagner Genres: Drama, Music Video & Concerts, Science Fiction & Fantasy, Musicals & Performing Arts Sub-Genres: Drama, DTS, Science Fiction & Fantasy, Classical Studio: Deutsche Grammophon Format: DVD - Color,Full Screen - Closed-captioned DVD Release Date: 08/09/2005 Original Release Date: 01/01/2005 Theatrical Release Date: 00/00/2005 Release Year: 2005 Run Time: 3hr 45min Screens: Color,Full Screen Number of Discs: 2 SwapaDVD Credits: 2 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 0 MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Subtitles: English, Spanish, German, French See Also: |

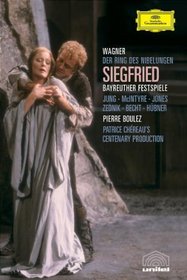

Search - Wagner - Siegfried / Jung, McIntyre, Jones, Zednik, Becht, Hubner, Boulez, Bayreuth Opera (Boulez Ring Cycle Part 3) on DVD

| Wagner - Siegfried / Jung McIntyre Jones Zednik Becht Hubner Boulez Bayreuth Opera Boulez Ring Cycle Part 3 Actors: Manfred Jung, Heinz Zednik, Donald McIntyre, Hermann Becht, Fritz Hübner Director: Brian Large Genres: Drama, Music Video & Concerts, Science Fiction & Fantasy, Musicals & Performing Arts NR 2005 3hr 45min Siegfried is the most eventful of the four Ring operas: the hero of the cycle grows to maturity, forges his father's broken sword Notung, kills the dragon Fafner and the dwarf Mime, takes the cursed ring, frees Brunnhilde ... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

|

Movie ReviewsSIEGFRIED; THIRD PART OF THE GREAT METAPHOR Josef Bush | Phoenix, AZ | 11/21/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "In many ways this is the most difficult of all the operas of THE RING to mount. Not only are the casting requirements as high as they are in any other part of the dramaic poem, but the premise of the thing is fundamentally incredible, fantastic, and cannot be presented realisically or even, sometimes, convincingly on any stage. SIEGFRIED can only take place in the mind, on the battlefield of metaphors and symbols. But, it is fascinating noneheless, to see what Boulez and Chereau did with it at Bayreuth, because even though they could not solve all the problems of the production to everybody's satisfaction, they did make remrkable and original choices; choices which were carried out in accordance with Bayreuth's highest standards, without compromise in artistic integrity. Their concept was rigorous and whole.

ACT ONE: When the curtains part, instead of a cave in a cliff face with a rustic forge in it, we find the solitary tinker Mime, standing, his back to us, at the edge of the metal grating that forms the floor of what appears to be (in metaphor) his pre-industrial artisan's Chop Shop in the woods. The grating in the area around his foundry is the same grating that we saw in DAS RHINEGOLD, through which Erda initially rose and then slid down in her final exit. It reminds us again of the stage; that this is a filmed record of a staged production and not a movie. To the left, a tall masonry edge, and to the right, three large, iron industrial cogwheels between riveted, lattice-type iron girders. Here, these not-quite-functional construction elemens used as design motifs, are reminders of the architecural vernacular of the Festspielhaus itself, or riffs on a 19th century building which was daring when it was first built because it utilized contemporary industrial techniques like iron beams for both suspension and support, which allowed the theatre to span largre spaces wihout using interior pillars; something masonry archiecture could not do. In this production, instead of using painted scenery to show a wood, the designer has creaed a thicket or grove of what looks like aspen, made of realisic arificial trees. The effect is not real, exacly, but shaply photo-realistic and solid-looking, and relates well to the other three-dimensional elemens in the set in such a way that the scene does not look as many "traditional" outdoor settings do, or like a painting in false perspective of a locale in a National Park. I looks more like an old 19th cenury photogaph of a real place, but colored. Plausible. Anyway, ugly old Mime, like an angry and resentful step-parent, is waiting for Siegfried to return, and kvetching because he's unable to forge a sword strong enough for Siegfried to use -- though Mime's convinced him to use it -- to kill Fasolt the dragon who sleeps on piles of ghelt stolen originally from the Rhinemaidens. Mime is sung and acted brilliantly by Heinz Zednik (who played Loge in DAS RHINEGOLD) and really the first half of this opera belongs to him. Not to the briliant Zednik, personally, but to the character of Mime. Here he's dressed in shabby clothes of the period, and wears a long apron. Although traditionally Mime is supposed to be a dwarf, he isn't presented as anything but an unfortunate old Tinker with thin hair and weak eyes behind glasses. That's reasonable or at least plausible because before there was the mass production of household goods, there were bands of itinerant Tinkers, menders and Smiths in both precious and base metals. These folks often roamed Erope, mending pots and farm implimens. They lived or camped outside cities and appear in EL TROVATORE as Gypsies and in LA JUIVE as Jews. Here embodied by Mime, they are the indigenous people of the ?Rhineland; the woodland and bog people. It is the hour before dawn. A mist hangs in the air. Mime hears Siegfried's horn somewhre off in the distace, and suddenly Siegfried appears wih a brown bear. That would be a Grizzly, because the German-Russian brown bear is the same speies, and standing should be about 11 feet high. Sadly, on stage the bear is always a man in a fur outfit, but as a metaphor it tells us that not only is Siegfried fearless, he is immensely strong and powerful and, to Mime, at least, terrifying. The bear leaves after only a few seconds. The point is it's nothing at all to Siegfried to capture such an animal and to bring him to Mime's sheler merely to torment and tease the old man. Alas, Siegfried laughs at Mime's terror and his own joke, but turns angry when the sword Mime has forged for him shatters almost at a touch. Siegfried insults the old man, snatches the food Mime offers and throws it at him. He slaps and cuffs Mime. Mime complains that the ungrateful boy has neiher affection nor respect for him though Mime has nurtured him. Zednik's faux-femenine whining povokes rather a distasteful reaction; one keen in Siegfried and familiar enough in ourselves. We neither like nor respect Mime for one who cannot command respect can only provoke contempt. ("Woe to the weak," as Hitler said.) Mime calls Siegfried "Son" but Siegfried says they can't be relaed because their looks are too different, and Siegfried says "I hate to look at you." It is an argument that goes on both in the music and on the stage, with much pushing and shoving and harsh movemen. It's a protraced and tumultous male duet made up of threats and half-threats between an old man of the working class and a youth of unceain paternity seeking to escape social obligations to an inferior. In contemporary terms this is the rage children who've been raised in foster care often feel towards those who've raised but not adequately or appropriately loved them. Manfred Jung sings Siegfried with gret assurance and expressiveness, while playing the character with a certain crudeness and adolescent naifte. His projection of voice matches his physical self; strong, muscular, agile. If you fancy Siegfried as the hero and prototype of the Germanic folk, you probably have taken your image from the Fritz Lang Nibelungen silents. But film is film and like all photography, benevolent, and a beautiful, half-naked youg man running through the woods with a weapon in his hand will always be a Superheroic atraction, and will usually make box office money. Opera, on the other hand, is the demanding medium it is: There, illusions are hand-made nightly. As Mark Morris said: Theatre is "Something people do in a certain space, for other people." And, of course, at great cost and with incredible dedication and effort. .Jung is well cast in this production because he's not the handsome, debonaire Froh (Siegfried Jerusalem) of DAS RHINEGOLD, or the tragic and willowy Siegmund (Peter Hofmann) of DIE WALKURE. He is who he is, and looks like the kind of young man you'd want on your side in a fist fight. He is not what Schwartzenekker would call, a "Sissyboy." But, when he goes off into the woods again to get away from Mime, and to give the old man time to forge the pieces of the broken sword his mother left for him, Mime despairs. The wretch hates his lot and wants the dragon's money as reimbursement for all the tme and trouble he's spent on this unpredictable, ungrateful, unruly and monstrously inflexible orphan. Under the circumstancs his decision to use guile to get that money seems reasonable. Stealthily, Wotan, disguised as The Wanderer has been listening to most of this, and he enters to play something like Twenty Quesions with Mime, who won't give him hospitality and wants him to leave. Donald McIntyre's performance throughout THE RING is outstanding, not only as an actor, but as a singer. I put actor before singer because in this production the accent is on his ability to portray the character of the man called Wotan through physical movement, and this he does superlatively. However, his singing should not be slighted, for it is very fine indeed; wonderfully well sustained, noble and most expressive. Unfortunately, what the role demands is that he express the soul of a man who is corrupt to the core. Yes, I'm afrid he won't please many viewers because he appears to have been directed to make no attempt to be charming, either to the characters on stage or to the audience. After all, Wotan is not merely an aristocat, but a god, and has no need to ingraciate himself with anybody. His voice, then, is like beautifully carved granite. (It is in DIE WALKURE, particularly, that the effect of his conrol of his voice pays off. When, near the end, as the first angry then sorrowful, then heart-broken father of Brunhilde, he puts her to sleep and, in effect, banishes her immortality, he gains our sympathy much as SIMONE BOCANEGRA does in the Verdi opra, through a display of profound and universal fatherly love.) Here, in SIEGFRIED, McInyre's tone, like his manner, is cool, slightly sarcastic and somewhat threatening. This is not merely recitative, but a quirk of Wagner's narrative declamation, the purpose of which is dramatic rather than lyric. There is no operatic lyricism in SIEGFRIED until the ultimate scene when, unexpectedly, we experience an orgasmic explosion of it that almost blows away everything that's gone before. Nevertheless, this prosaic dclamation suits Wotan's appearance, for now he's dressed as a counry gentleman in a walking outfit. Mime reacts to him (a a one-eyed man with a squint) as any poor, working peasant would to a plainclothes policeman, or tax-gatherer or upper-class grifter with notions of entitlement. Though he cannot adequately grasp the horror of his predicament, Mime has every reason to be suspiciouc because Wotan, through Sieglinde, has atached Siegfried to him the way a predatory carnivore wasp attaches one of her eggs to the abdomen of a paralyzed cockroach she's dragged into her den. She does this in order to insure that her grub, as it develops, will be able to eat live and therefore fresh food until it reaches adulthood. By then the cockroach will be an empty husk. All this has been a thinly-disguised display of sadomasochistic homoeroticism and dominance, and reminds one of Berg's WOZZEK. However, by the time Wotan leaves, Mime understands that he has been visited by not only a god, but by the ruler of all the immortals, and that he has been threatened. The warning was devine: He must not interfere with Siegfried's progress, for if he does he risks Wotan's anger. Meanwhile, the stage has modified itself yet again. Brick walls, windows and iron grates appear. When Wotan leaves, a huge, steam-powered hammer appears, sparking and smoking. Seeing this, Mime has a frightening vision of the Giant and Dragon Fasolt, and goes through a series of occult frenzies. Out of them, or by means of them he attempts to teach the newly-returned Siegfried what fear is. It doesn't work. The two men are in a brick-and-mortar foundry now, with the woods just beyond a wall, and eventually, after a struggle, Siegfried takes the pieces of the sword from Mime and begins to forge them himself. The atmosphere is sooty. A monumental flywheel appears behind one of the walls. Siegfried files the blade into powder, melts it with the heat of the kindling he's taken from a forest ash tree (Wotan's totem) and casts the sword. Then he forges it with the steam hammer which is, again, Wotan in metaphor. Sparks fly and the great wheel turns as Siegfried's mechanized foundry produces Necessity, Siegfried's god-given weapon in a crecendo of terrifying masculine sound. The synthesis is perfect: The forge is merely a clockwork replica of the once world-famous steam hammer at the Krupps steelworks. As Siegfried toils, Mime, shining with envy and hate, decides to poison him once he's killed Fasolt, and he sets a-mixing. Mostly, he does this while standing in the lower spaces of the floor, which spaces hold all the props he uses. During this act, Chereau has Zednik "in the hole" (or barrel) for most of the action. It lends an illusion of height and physical power to Jung and McIntyre as they torment the old man. Until recently people felt that this act which depends on the humiliation of Mime, was a thinly-disguised expression of Wagner's personal anti-semitism. That notion is fading because now we have available to us not only Wagner's articles on French Opera, translated into English, but new recordings of Halevy's The Jewess (LA JUIVE: Antonio de Almeida, Phillips) which was the most popular opera in Paris when Wagner was there learning his craft, and which he saw in several productions over time. He admired LA JUIVE greatly and openly, and learned much from it. Much of what he learned he displays here in SIEGFRIED. I believe Wagner fashioned his character Mime after what he saw in LA JUIVE and in other nearly-forgotten works, and realized that the composers and librettists of these shows, used toiling people of low station and little wealth symbolically. Then, parcipatory democracy was unknown in Europe and struggled for live across the seas in the sometimes dis-United States of America. They felt that these sufering people were bieng abused and exploited by militry bullies working in the service of narcissistic, morally bankrupt and paracitic elites of the sword, the cross and of commerce. In visualizing this production of THE RING, it appears that the Director, Conductor and the Producer sought to evoke something out of Richard Waner's tastes and values as they would have been at the time, and to project a contemporary feeling through all that. Written and produced in an era when railroads were just beginning to cross and re-cross Europe, the designers here attempted to evoke an atmosphere of hot iron and noise and clouds of steam and smoke, much as the French Impressionist painters experiened it as they saw huge, black locomotives thundering through Paris. They focused on his career as a social rebel and revolutionary who'd been exiled from his native counry as an enemy of the State. As a sworn proto-comunist or socialist -- which he certainly was -- he knew he would have to rehabilitate his professional image if he intended to become a financially successful composer, and over time he did so, becoming therefore, a crypto-socialist. That is, a socialist whose purposes are given in a kind of code. Hence, the mythological clap-trap of the Sagas became the vernacular with which he disguised his motivation; which was an unrelenting hatred of the aristocrat class, and a will to conribute to its destruction and replacement. Nevertheless, Mime is created fatuous and ineffectual in order that Siegfried, who is god-driven, may seem inevitable. For in his might he can... "...fettle for the great, gray dray horse His bright and battering sandal." Therefore, unable to imagine fear or to tolerate hesitation, Siegfried reconstructs his sword and with it slices Mime's anvil to pieces as the curtain falls with a tremendous din. ACT II: Night in the woods. Two similarly dressed and fairly obvious rogues are seen prowling through this artifical but convincingly 3D forest. They are discovered to be Wotan and Alberich. Difficult to tell them apart. Which figures because their intetions are virtually identical. Like scavenger ravens, they are prowling through the thickets before Fasolt's cave in order to either frustrate or to profit by Siegfried's attempt to kill the dragon. Fasolt, nevertheless, is vaguely aware both of them and their desire for his gold, but unseen, he simply snores that he wants to be left alone, to sleep. All this takes place in nearly pitch darkness, until Fasolt allows us to glimpse, not the treasure itself, but the illumination given off by it. Suffused with covetousness, both Wotan and Alberich leave, separately, though intending to return after Siegfried has accomplished his objective. The lightening in this production is so remarkable that, in this instance, instead of illuminating what is, after all, only a stand of artificial trees, it intensifies the illusion of a woodland glade by directing the light to fall from above, like moonlight, and to filter through the leaves, creating patches of dappled light on the stage. This lends versimilitude and credibiity to the entrances and exits of the characters -- charactes who are luking about, spying and attempting to hide from one another. Soon, Siegfied and Mime enter, still quarreling irritably, and at one point Mime climbs a tree to escape Siegfried's anger. Eventually, though, Mime decides to leave Siegfried to himself and to the dragon, and finding himself alone for the very first time, Siegfried allows us to see himself as he is; an adolescent mooncalf. We know immediately in our hearts, that he's about 15. Behaving as adolescents so often do, he stumbles around, trips, ponders his origin, sighs for his mother, throws hmself on the ground and looks at the sky. Jung's characterization is something! His movements throughout are so adolescent. In the naturalness of his amorality Siegfried is like so many gawky, intense, self-absorbed boys in his fits and starts of coltish gracelessness. In just this one scene Jung makes us forget everything unpleasant about the character we've seen so far, and provokes a sympatheic tenerness. It's the awkward beauty of callow introspection taking place in what appears to be an aspen grove. So clumsy is he, so endearing in his testosterone haze -- he is Everyboy shuffling and smirking, lined up for his first military uniform -- that when the Woodbird sings, through Siegfried's transparency of soul we can see the music enter and animate his body. With yet another coup de decors, Chereau has chosen to let Siegfried ifnd the bird itself (a live one) half-way up a solid tree, in a rustic little wodden cage with a handle. The Woodbird becomes, metaphorically, a portable radio. By means of this device, this wonderful scene shows us how well Wagner understood what happens when a young man first becomes conscious of Music. It talks to him through his nervous system even though he cannot either understand what it means, or duplicae its effects with instruments he himself plays. Neither with a reed pipe he makes, nor with his own horn can he match the beauty of birdsong, but his horn does wake the dragon, and it appears, ready to challenge the intruder. In this production the dragon is used as yet another stage device dedicated to the genius of Wagner. Here, it is not only a very large and very solid piece of stage equipment, free-standing and free-wheeling, it has flapping wings and ability to rare up and spew smoke. This apparatus appears to be an accurate reproduction of the original basilisk-headed stage machine made for the first production of this opera, in this very Opera House. Remarkable as that is, as a solid machine it fits into this past-friendly, Post-Modern production perfectly because like everything els it has a photo-reality and a tangibility. When Siegfried fights the machine he is in scale as an infantryman would be to a talk on a batlefield. He follows it as it is manoueered around the stage by number of dark-clohed, anonymous men, and sttacks and kils it as a guerilla fihter would do, by stabbing its underside. The effect is convincing withut being in any way eiher spooky or illusionistic. How many productions of this unique opera -- which until now has seemed to be nothing so much as an interminable quarrel between five short-tempered, unpleasant and unsympathetic men, has it not? How many have boasted satisfying dragons? More often than not one sees a show with an idiotic puppet that wouldn't intimidate an infant. I've seen a flopping, rubberized pneumatic assembly of bightly colored inflated vinyl bladders on stage, like a display ape on the roof of a tire outlet garage. No! Siegfried deserves a good dragon, even if the show is only make-believe. At any rate, after Siegfried kills the thing, staggering, Fasolt in his own giant's form emerges to warn him against the dire power of the Rhinegold and the ring, and then to fall and die, centerstage. Soon, both kites, Wotan and Alberich emerge from their respective thickets, to comment on and to lust over the gold's power, which power appears to be presently Siegfried's alone. Somehow the boy's been splashed with burning dragon blood, and licking it he finds he is able to understand the Woodbird's languge. She sees all from above and warns him. After wheedling and threatening each other for a bit near the body of the fallen giant, Wotan and Alberich disappear as Siegfried appears from out of the dragon's cave, bearing the helmet of invisibility and the ring of power. Never having had possessions, and puzzled by these new ones, Siegfried flops on the ground to examine them like an ape with a Swiss watch. Then, Mime returns, jubilant to see the treasure in the boy's lap, and grinning, he promptly attempts to poison him. The bird warns Siegfried, and he promptly kills the old man. For reasons best known to himself alone, Siegfried drags the copse off to hang it as a Shrike might, on the branch of a tree. And so, finally, Siegfried finds himself in a moonlit clearning, alone but for the sprawling body of a giant he is unable to drag away. As he puzzles about all this, the Woodbird tells him about Wotan's sleeping daughter and without the slightest hesitation he looks about, sees a bright-lit cleft in the trees far away, and sprints off toward it as the curtains close. ACT III: In an instant, that is, in a flash of stage time, we find ourselves somewhere else and notice that wherever that may be, Wotan has beaten us to it. He's striding through the swirling murk, dressed as before, and looking a great deal less than godly. In this production he's aged greatly from the one-eyed eagle he was in DAS RHINEGOLD and DIE WALKURE, into rather a furtive character, like a used dragon salesman. (It's all McIntyre's skill.) Abruptly, he finds an outcropping of pale rock and, calling out for Erde, he jabs his spear into the earth at its base. It is at this point that you must prepare yourself for one of the most remarkable entrances and performances not only in SIEGFRIED, but in the entire production of THE RING. Erde, portrayed by Ortrun Wenkel appears as a thick, unrecognizable effusion. She spurts or oozes out of the ground much as pillow lava roils up out of a fissure in a tectonic plate under the Pacific. You cannot tell her head from her hips, her shoulders fom her knees. She rolls onto the stage like the mind of a psychotic feather bed -- in pale, soft lumps, tumbling slowly, clumsily and irregularly -- almost unrecognizable as a human being. Yes, this is the same Erde we irst saw in DAS RHINEGOLD, but now, almost unrecognizable. Now, in some productions of this opera the Wotan chaacter stops, decorously if petulently, to confer with the disembodiedd head of a lady with a blue and/or green face, wearing a fanciful headress, who sings from a hole in the stage. But here, the somnolent, taciturn nature of the Earth Mother is expressed in a robust if unpleasantly frank physical interaction with or against teh Sky Father. Somehow, in an intercouse with Erde, Wotan begat Brunnhilde at least, and possibly all her sisters. In this scene, Chereau has managed to display both the repulsion and the attraction of Sky and Earth. What we see is not quite a wrestling match, but somehing unique in its depiction of Wotan as an egoistic bully who's priapic spear -- the lightening bolt -- is the sceptre of his erotic and cretive power over the entire prostrate world. Though he finally and with great difficulty rouses Erde sufficiently to respod to his inquires -- and he even de-veils her with a sly callousness shocking in itself (the efect is that of stripping the ancient female naked) Erde is unable to tell him anythng other than that he is likely to be disappointed in his pursuit. Wotan doesn't care even about the approaching end of the rule of the Immortals. He only wants to control that end and to influence the future. Wotan frees Erde and she exits much as she entered, rolling away like a strangely animated ball of mud. What a performance! Both strenouous and visually incredible. But, through it all, Wenkel's singing is wonderful; even if and when we wonder how she can breathe or articulate. What an artist! In no time then, Siegfried stumbles through, led by the Woodbird who, seeing Wotan, promptly flies away. Wotan attempts to bar Siegfried's passage but the young hero is as contemptuous of the old god as he was of old Mime, and rudely manhandles him. When Wotan objects, Siegfried shatters the spear and Woan slinks away like a whipped cur. Alone, ;briefly, Siegfried sees the ruddy glow of the magic fire protecting Brunnhhlde, and with a sort of shrug, strides off into the blazing cucible. And now, the second half of ACT III and the pinnacle of this most ambitious of opera, SIEGFRIED, and indeed the glittering jewel set upon the band of THE RING. Everything that has gone before is, in an instant, blown away like motes in a breeze, the moment Siegfried like a beam of morning light, strides into that area dominated by the monumental ampitheatre of rock where the Valkyres once plied their ghastly trade. But now it is early, dewey morning, and a sense of tantalizing but peaceful expectancy like a Spring green shimmer lies over everything. Brunnhilde lies asleep within the embrase of this structure, but hidden from Siegfried's sight by a shadow that obscures the caldera's interior from him, but not from us. But here I stop. Beyond this point my poor powers of description fail. We know or remember how it goes, or at least we have the libretto at hand and we know that Siegfried finds an armed figure asleep and removes enough of the armor covering it to discover it is not a man, but something else. He has never before seen a woman and prohibited by ancient incest taboos, he hesitates to touch her breasts. But... Eventully he does touch her. He kisses her and she wakes like the Beauty in the fairy tale and, she, Brunnhilde, seeing him -- not the first man she's seen, but the man her father's power has destined her to love and serve -- she hesitates. They are both frightened, abused and neglected children, but Nature is kinder than Fate, and eventually they reject fear and cling to each other in an appotheosis of biological inevitability disguised as young love. This happy joining together is easily one of the greatest love scenes ever written: It thrills the heart and satisfies the mind. There are many good recordings of this duet, and we have all heard it sung beautifully on the radio. But, it is that quality of depth of artistic perception that separate this production from most. Although one is not likely to see a production of this demanding work sing by unaccomplished performers -- it is technically far too demanding -- what one sees too often is hackneyed stuff; you know, some zoftig woman with pointed breasts and a mop of wild hair, wearing a long, transparent frock, being coyly but lewdly serenaded by a tall job in a fringed leather outfit. They carry on at great length in front of acres of scenery, painted to resemble any Yosemite, and by the time they clinch it is as though they'd been doing the O'Horgan grope'n grovel somewhere in the Baja for Antonioni; and like a methodist family picnic party discovering hippies fornicating in the nearby bushes, we've been gaping, in open-mouthed disbelief. What's missing beside tambourines? Pink Floyd? Consider: the sexual/emotional awakening of these two innocents is never predictable or ever inevitable. Whatever your imaginery picture of Siegfried and Brunnhhilde may be, Gweneth Jones and Manfred Jung are perfect here because the entire production has in every detail been set up for them, designed around them. Jung we have become accustomed to, but Gweneth is -- like sunrise in the tropics -- sublime. The costumer has defied traditon and put Jones in a deceptively simple gown that is like all the gowns of all the angels and virgins in Quatrocento Florentine painting, and her hair falls across her shoulders and bosom with the chaste artlessness of a Murillo Madonna. The gown is Modesty, which of all qualities attributable to beautiful, chaste women and to worthy men, is the most flattering and the most arousing of all. On stage, the light around them is a perfect radiance and perfectly modulated so that at the duet's summit, the effect is like watching a love scene in a Pre-Raphaelite painting by some opium-obsessed Scotsman. Which effect is much as Wagner himself may have intended it, for when the curtains close with a rush on their first caresse, our eyes are wet with tears of joy and thanks. NOTE: It appears they aee no longer pressing these discettes. Don't let that stop you. Buy this RING used, or steal any of it if you have the opportunity; particularly this SIEGFRIED. Life is short." |